From the “Contrescarpe”, I only knew this name which resonates well in a refrain of the song “La Langue de chez Nous (The Language from our Home)” by French Singer Yves Duteil:

” Et du Mont Saint-Michel jusqu’à la Contrescarpe… (And from Mont Saint-Michel to the Contrescarpe…)”

” Et de l’île d’Orléans jusqu’à la Contrescarpe… (And from Orleans’s Island to the Contrescarpe…)”

I was in Paris for a few days at the very beginning of January for professional reasons. I was staying in the Sorbonne district, not far from the Pantheon, which I hadn’t visited since I was twelve. From the Pantheon, my steps led me to the Place de la Contrescarpe which is as charming as its name is lilting. It’s a round square, not too big, with beautiful trees and a fountain in the middle, surrounded by cafés and restaurants, which reminds more of the heart of a village than of a big capital.

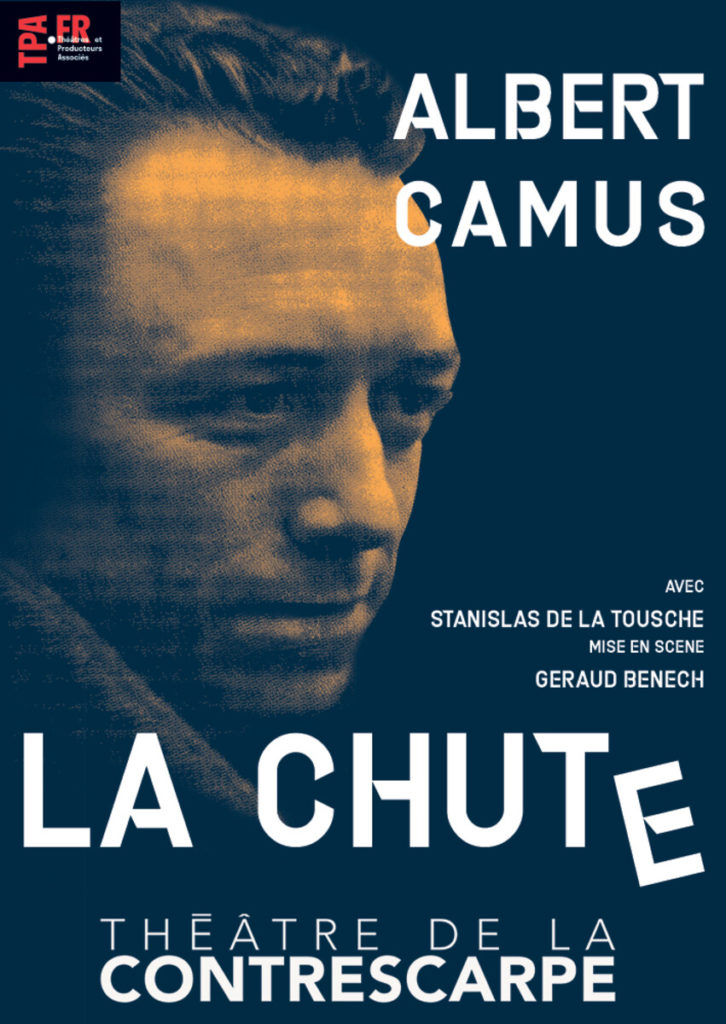

A few steps from the square, I came across the Théâtre de la Contrescarpe. My evenings were free and they were playing “La Chute (The Fall)” by Camus the next day. I booked my ticket online.

So, I came back the next night. I walked down a staircase into a very small theater, and, since seating was free, I took a front row seat. There was only one actor, the excellent Stanislas de la Tousche, and he acted a monologue, an adaptation for the theater of Camus’ text by Géraud Bénech. The staging, sober and effective, played on the contrasts, between white and black.

The main character in “La Chute” is Jean-Baptiste Clamence, who is at the counter of a disreputable bar in Amsterdam called “Mexico City”. Between beer and gin, he accosts the other customers, preferably French like himself, and tells them about his life. He was a brilliant lawyer in Paris, defending the widow and the orphan. A tenor of the bar, generous when he did not submit his fees to his poor clients, but also seductive and charming. According to him, few women resisted him, and although he did not get attached, none of them reproached him.

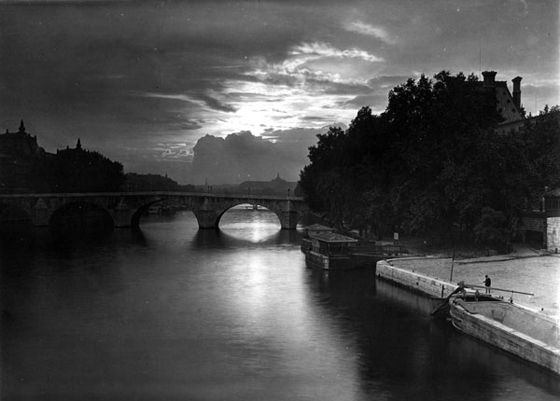

But one evening, as he was returning, happy, from visiting his mistress of the moment, he crosses the path of a shadow on the Pont Royal. She seems to be a woman in distress. He is intrigued but continues his way. Suddenly, he hears the sound of a body falling into the water. He stops. A scream resounds in the river. He wants to do something but hesitates. The cry goes away. Too late, too far.

Confronted with his inherent weakness, Clamence sees his life and his successes in a different light. Everything was so perfect, but when it was time to act, he remained motionless on the quay of the Seine. He begins a downward spiral that takes him to the underbelly of Amsterdam’s red-light district.

At the end of his monologue, he refers to the famous panel of the Just Judges from the altarpiece of the Mystic Lamb by the Van Eyck brothers, stolen in Ghent in 1934 and never found. Like all of us, “humans too humans”, he compares himself to a judge-penitent, clear on his failings and unable to but resign himself to his punishment of decline.

I left the theater, a little stunned, and walked to the front of the Pantheon, noticing its pediment that proclaims, “Aux Grands Hommes La Patrie Reconnaissante (To Great Men The Grateful Fatherland)”.