Antwerp is the city where my father was born, where my paternal grandparents met and got married before moving to Brussels after World War II. My father, born in 1941, had been brought to stay for a few weeks in the clergy house of a village in the surroundings to avoid the « flying bombs », the V1s and V2s that the Germans were launching towards the city and the port after they were liberated by the Allied Forces. Despite this precaution, one of his first childhood memories, as he told us, was to have been dressed standing on a chair because the blast of the explosions had shattered the window glasses in the room where he was sleeping.

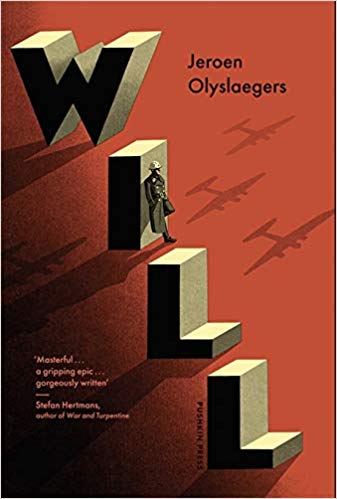

The novel « Will (Wil) » by Flemish writer Jeroen Olyslaegers is a deep-dive both captivating and troubling in the city’s past during World War II. The narrator Wilfried Wils tells his story from two perspectives. First, as an 18-year-old young man, an admirer of Rimbaud, who joins the Antwerp police force to avoid being drafted for compulsory work in Germany. And then, intervening here and there, as an old man, an ignored poet, writing to his great-grand-son to try to disentangle his memories.

At the beginning of the story, the young recruit is forced to participate in a night raid in the Jewish diamond traders’ neighborhood. He doesn’t know well how to react, stuck between the Gestapo’s presence and the mothers and children begging for mercy. Towards the end of the book, he observes powerless the aftermath of the Rex movie theater’s destruction by a V2-bomb on December 16, 1944. There would be 567 victims, 296 allied soldiers and 271 civilians.

Between these two events, Wilfried balances without much of a clear vision. His former French tutor « Meanbeard » brings him into the bars where the collaborationists meet and where the SS officers dance with easy girls. His colleague Lode Metdpenningen, who is also the brother of his girlfriend Yvette, tries to attract him towards the Resistance circles. Wilfried ends up regularly bringing food and books to Chaïm Litzke and his family, Jews hidden by Lode’s father. But this forbidden and risky assistance might very well be motivated by payments in diamonds. Our policeman’s aunt, for her part, will switch very quickly from an SS Oberscharführer’ arms to those of an American sergeant.

One evening, the Antwerp police needs to make a raid in the Jewish quarter. But this time, it is not there merely to “maintain order” while the Gestapo and its minions knock on doors. No Germans are present on that evening. It is the police itself which needs to wake-up, gather and embark the families towards the death convoys. An indelible stain on the city’s memory. It is only very late, in 2007, that the mayor would offer apologies on the city’s behalf, not without stirring political controversies. A stain also in Wifried Wils’ soul. When she commits suicide, his grand-daughter, a rebel he adored, left these short words: « Grand Daddy is a bastard ». Yvette who became his wife drowns in alcohol and the rest of his family abandons him.

Jeroen Olyslaegers eye-opening novel makes several references to the painting Mad Meg (or Dulle Griet in Flemish) as a symbol of that period when Antwerp didn’t know where to turn in the middle of the carnage. This masterpiece by Pieter Bruegel the Elder is in the small but splendid Mayer van den Bergh museum. It is one of the many reasons to visit a superb and lively city which has left its troubled years behind.