Singapore enjoys a reputation for excellence and efficiency. On my recent trip, this was confirmed as soon as I arrived at the airport. Nowhere else had I experienced such fast and pleasant immigration control, all electronic. On the way to the hotel, everything was still perfect, right down to the screens instructing the taximan to drive with caution.

Arriving in the evening, I went for a stroll along the banks of the Singapore River, a short walk from my hotel. A light breeze made the muggy heat more bearable. After sitting down to some satay skewers and a cold beer, I strolled over to the Fullerton Hotel. Once under the bridge, the three pillars of the Marina Bay Sands come into view, surmounted by the elegant horizontal arrow that caps them and makes this brilliant feat of modern architecture, inaugurated in 2011, one of the new symbols of this city-state, which in just a few decades has risen to the top of the rankings of the world’s richest and most developed countries. The following evening, I passed Marina Bay to discover with my brother the electric and musical enchantment of the giant artificial trees (“supertrees”) that are the major attractions of the “Gardens by the Bay” nature park.

Singapore is a dazzling success story of modernity. In just over two centuries, the former British naval warehouse has developed into a city of excellence, where the cultural melting pot of Chinese, Indian and Malaysian populations seems to have blended harmoniously. The city’s superb museums, the Asian Civilisations Museum and the National Gallery Singapore, offer a glimpse into the city’s rich past at the crossroads of civilizations and religions.

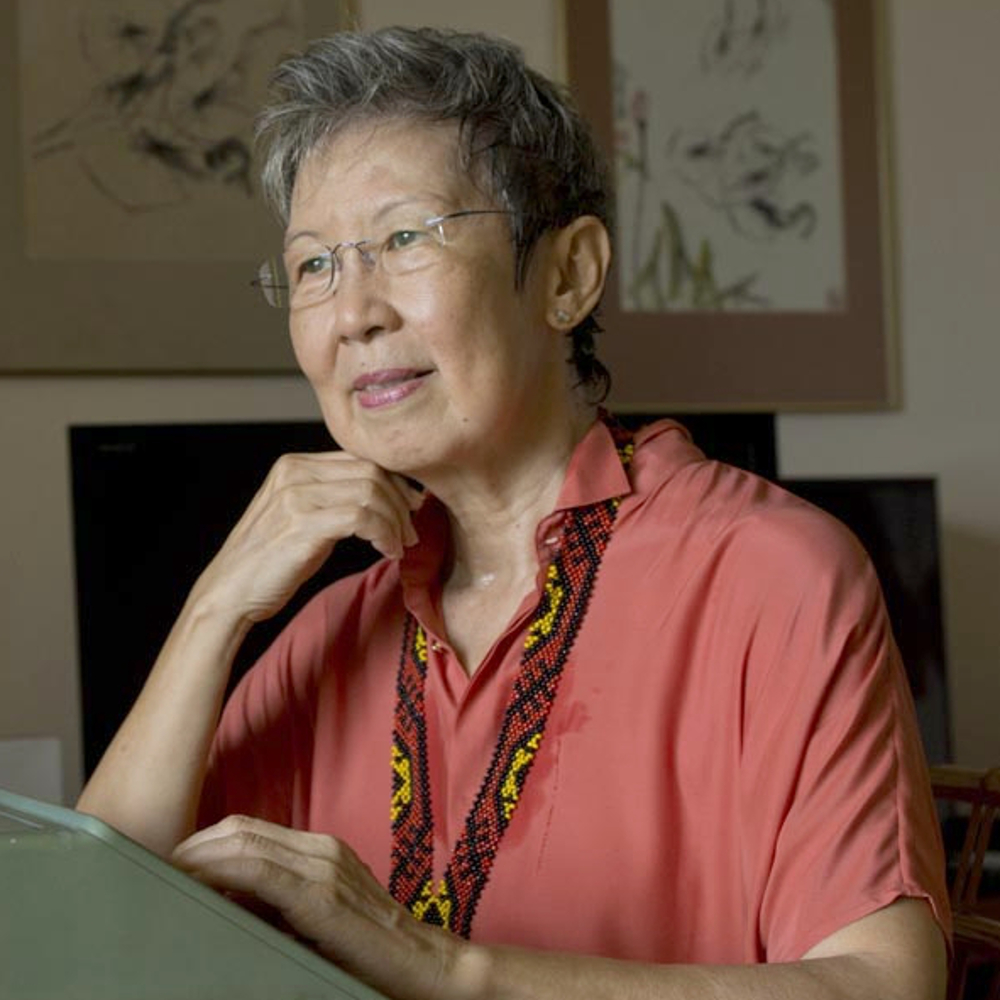

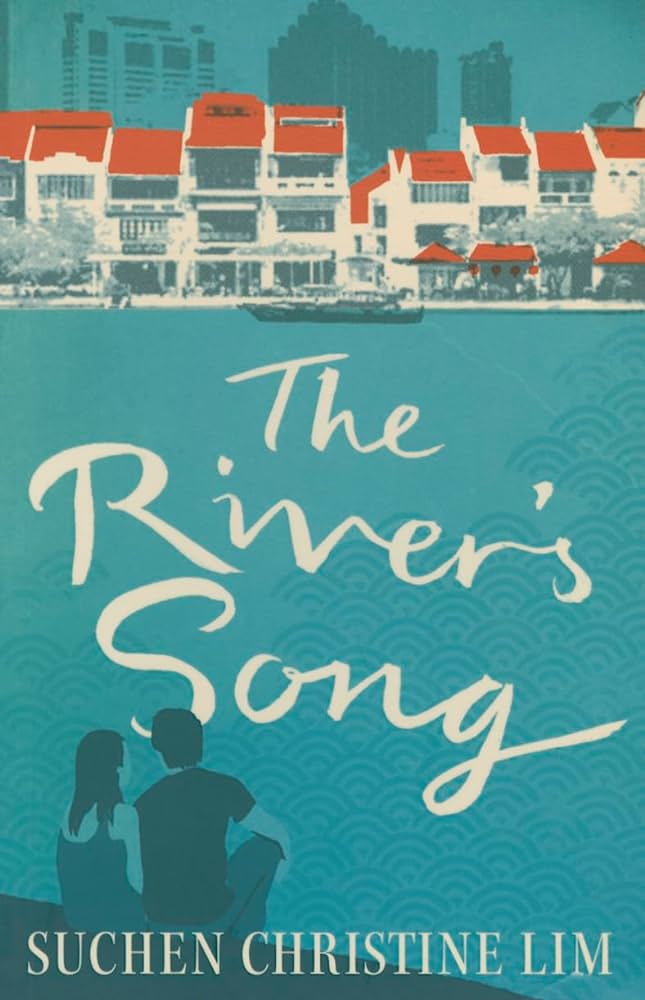

But it was by delving into Suchen Christine Lim’s novel “The River’s Song” that I learned even more about the history of the city and, in particular, the districts along the Singapore River. In the 60s and 70s, Ping is the natural daughter of Yoke Lan, a pipa player – a Chinese plucked string instrument similar to the lute – who performs in Chinatown cabarets and nightclubs. Weng, who plays the flute, is the son of a coolie who unloads the boats that dock on the river. Ping attends the pipa classes that Weng’s father gives in the evenings. Ping and Weng live in the poverty of the insalubrious, illegal housing that accumulates on the banks of the river. Leaving childhood behind, they discover their love. When Yoke Lan marries a wealthy Chinese merchant, she takes her daughter to a beautiful villa, but the mother, concerned about appearances in her new environment, introduces Ping as a distant niece and forbids her to return to find Weng at the water’s edge.

The government launches a policy of “cleaning up” the riverbanks. Land values rise and the company of Yoke Lan’s new husband evicts Weng’s family from the illegal dwellings in which they had been living. They are promised apartments in the high-rise public housing projects being built by the city, but the squatters don’t want these modern cages and protest. Weng, who has learned to write, records their grievances, and is arrested by the police as one of the leaders of the movement.

While he spends a few months in prison, Ping is sent to study in a college in the United States, where she continues to learn pipa and then becomes a professor in the musicology department at Berkeley. Decades later, she returns to Singapore when her mother dies. The city, and her family, have changed, but she is reunited with Weng when her pipa and his flute resonate together at Yoke Lan’s funeral ceremony.

I spent my last afternoon in Singapore wandering around Chinatown. The area has been transformed and has become a tourist attraction, but probably less so than the nearby riverside. I enjoyed trying to find traces of the period when Ping and Weng used to get together to try and earn a few cents by selling the vegetables that fell from the crates brought to the market. As the frescoes painted on the walls of the Thian Hock Keng Taoist temple remind us, behind its cutting-edge modern facade, Singapore remains a melting pot where the hopes and dreams of numerous immigrants from all over Asia collide and melt into the mold of this city-state that aims to be so perfect.