When I first visited Dubrovnik, the Pearl of the Adriatic was still in Yugoslavia. I was amazed to discover this medieval city set within its walls between the hills and the blue of the Mediterranean. Inside the ramparts, you stroll along Stradun, the main street with its shiny paving worn by the passage of centuries. You look for a little shade to better appreciate the architecture of the monasteries and palaces that line up between the city’s two gates. I returned to Dubrovnik with my family about two years ago. The city is as beautiful as ever, even if the tourists – particularly those attracted by the sites made popular by the “Games of Thrones” series – are numerous. In the afternoon, we headed off to the splendid island of Lokrum to escape the crowds and cool off with a swim. We returned at the end of the day to walk around the city walls before having lunch in one of the town’s little streets.

On this last visit, we had come from Kotor, crossing the border between Montenegro and Croatia, a reminder of the break-up of the former Yugoslavia. Between my two visits to Dubrovnik, I had other opportunities to travel in the region. I remember that during an express crossing in the summer of 1989, driving from Hungary to Greece in less than 24 hours, I was struck by the fact that the tolls on the Yugoslav freeway were chalked up on blackboard, because of the galloping inflation. In 1993, I also spent a month in Istria, in northern Croatia, working as a volunteer in a camp for Bosnian refugees, while war raged further south.

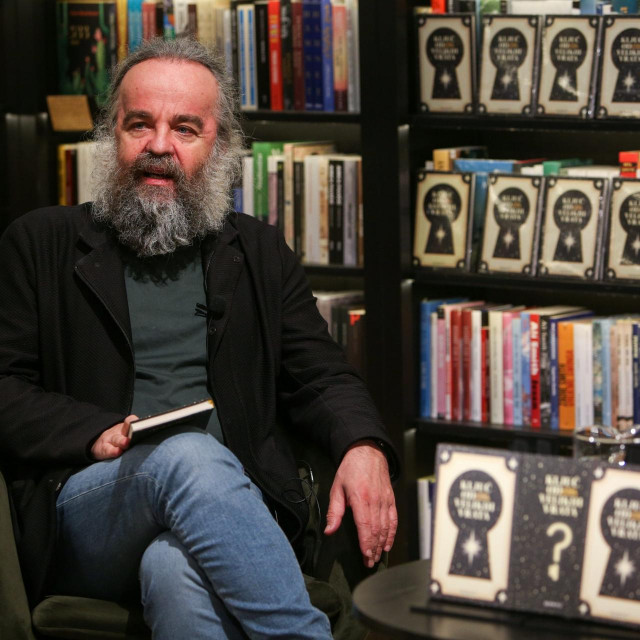

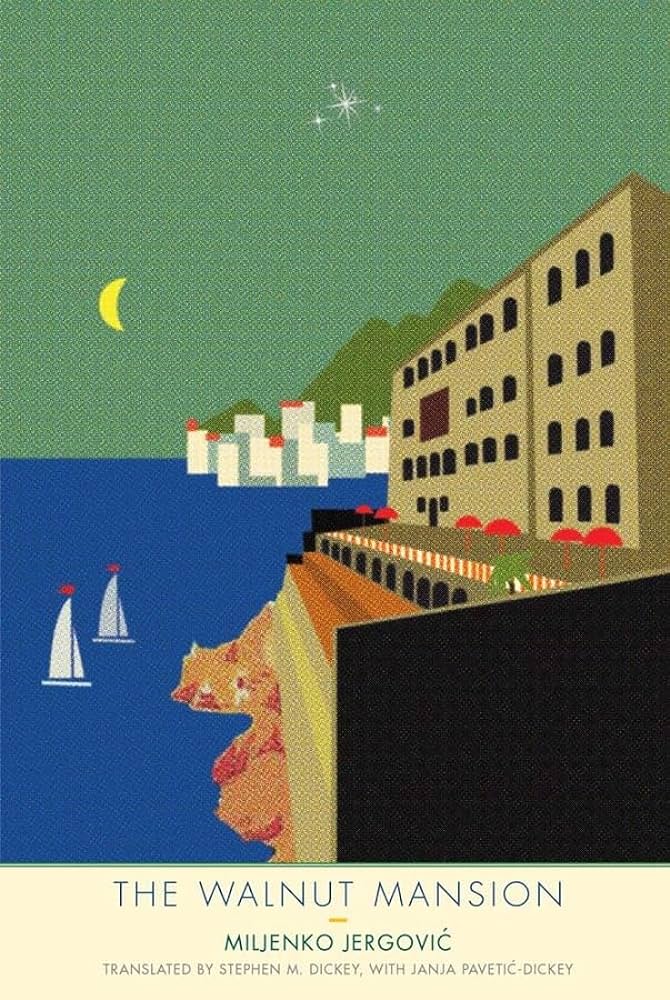

I rediscovered Dubrovnik and deepened my knowledge of Yugoslavia’s complicated history by reading “The Walnut Mansion” by Miljenko Jergović. Born in Sarajevo and living in Zagreb, the writer recounts, with humor and generosity, the life of Regina Delavale, who died in Dubrovnik in 2002 at the age of 97. He tells the story in reverse, from the near-centenarian’s death in an hospital to her birth in 1905.

This backward journey is surprising at first, but it allows us to understand some of the events with the benefit of hindsight. As the chapters unfold, we discover Regina’s family members, those who survive her, and those who died along the way, notably during the tragic conflicts that did not spare the Balkans in the 20th century, from their exit from the Austro-Hungarian Empire to the break-up of Yugoslavia. Jergović leads the reader backwards through this labyrinth, taking him by the hand as he sketches out the history of the former Yugoslavia. Some of Regina’s brothers end up – and die – on opposing sides, Chetniks and Ustashis, during the Second World War. At the same time, her husband shared a hideout in Bosnia with a wealthy Jewish shipowner. A sailor, he will spend his life on the seas and in the ports, and becomes attached to another woman in America, leaving Regina alone in Dubrovnik. In May 1980, the whole city comes to a standstill, as if in awe and fear for the future, when the radio announces Tito’s death.

Dubrovnik, with its neighborhoods where everyone knows and observes each other, is the center of the novel, which nevertheless radiates throughout the region, for example to Sarajevo, where Regina’s daughter Dijana will run away to live with her boyfriend in the 1970s. In the final chapter (but the first chronologically, in 1904), Regina’s grandfather commissions a craftsman to carve a doll’s house from walnut. This will be his birth gift to his granddaughter, who will live through an eventful century, watching her house fill up before emptying, as events unfold, oscillating, like the novel, between comedy and tragedy.