Over the years, this has become a ritual during our summer trips back to Belgium. Often with the whole family, we go to see the play performed outdoors in the ruins of Villers-la-Ville Abbey. The remains of this abbey, founded by Bernard de Clairvaux in 1146 and sacked during the French Revolution, lend themselves perfectly to the theater. On July and August evenings, the sun sets at around nine o’clock. Depending on the weather surprises of Belgian summers, spectators sometimes arrive with a blanket to keep warm, and hoping not to have to open their umbrellas.

The magic soon begins. The old stones of the abbey provide a natural backdrop for the classical and historical repertoire performed. The half-light and then the night allow the shadows and colors to reinforce the drama of the plays. The acting – which at least once every evening has to be interrupted while a local train passes by – is generally excellent. Often, from one act to the next, the audience moves through the ruins. I remember many final scenes played out in the choir of the abbey church.

I’m sure I’m forgetting some, but I think I’ve happily attended the following shows over more than thirty years: Cyrano de Bergerac (Edmond Rostand), The Name of the Rose (Umberto Eco), Dracula (Bram Stoker), Frankenstein (Mary Shelley), L’Avare (The Miser) (Molière), Caligula (Albert Camus), Le Bossu (On Guard) (Paul Féval), La Reine Margot (Alexandre Dumas) and Milady (Alexandre Dumas adapted by Eric-Emmanuel Schmitt).

It was often my father who organized these evenings, and we would accompany a large family group after a meal in their garden. This summer, we turned the tables and my wife Céline and I invited our parents to see Lucrezia Borgia, a play written by Victor Hugo.

Victor Hugo himself visited the Villers ruins several times between 1861 and 1869. He was inspired by these traces of a bygone era, which his romantic imagination wrapped in mystery and drama. He left us several drawings of the abbey, and a passage in Les Misérables was inspired by his visit to the dungeons.

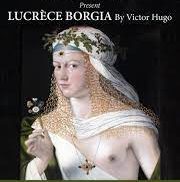

Lucrezia Borgia is a name that even today symbolizes beauty, but also depravity and lust. First of all, she is a Borgia, a name that has become synonymous with the worst excesses of the papacy during the Renaissance. She was the natural daughter of Cardinal Rodrigo Borgia, who would become pope under the name of Alexander VI. She was married three times, serving as a bargaining chip for political alliances between great European families: Sforza, Aragon and Este. Her second husband, Alfonso of Aragon, was murdered on the orders of his brother, Caesar Borgia. A whiff of crime, adultery and even incest followed her.

Hugo’s play undoubtedly contributed to this dark legend. Gennaro, who knows nothing of his origins, meets Lucrezia at a ball in Venice and is seduced by her beauty. She recognizes the young aristocrat as her son, the fruit of her incestuous love affair with his brother. Lucrezia’s husband, Duke Alphonse of Este, sees Gennaro as his wife’s lover and wants to eliminate him.

This impossible triangle plays out wonderfully in the shadows and light of the night in Villers, and the drama weaves its way from sword to poison, until we discover behind the depraved Lucrezia, a mother dying for not having been able to love.