What is Norway’s secret? Its population is just over 5 million. Yet the country and its people seem to shine on all fronts. During our recent trip, I admired the architectural marvels of the capital, the Opera House and the newly opened National Museum, set at the bottom of the Oslo Fjord. In sports, it might not appear surprising that this small country has been leading the Winter Olympics head and shoulders for years. But recently, they have also shone in athletics, and in soccer, everyone knows their young center-forward prodigy. The world chess champion is Norwegian.

Of course, the wealth brought by the oil windfall must have something to do with it. These resources, well managed, have transformed in two generations this splendid but somewhat marginal country between fjords and mountains on the northern borders of Europe into a society that punches above its weight on the economic, political, sporting and cultural arenas. But there must be something more.

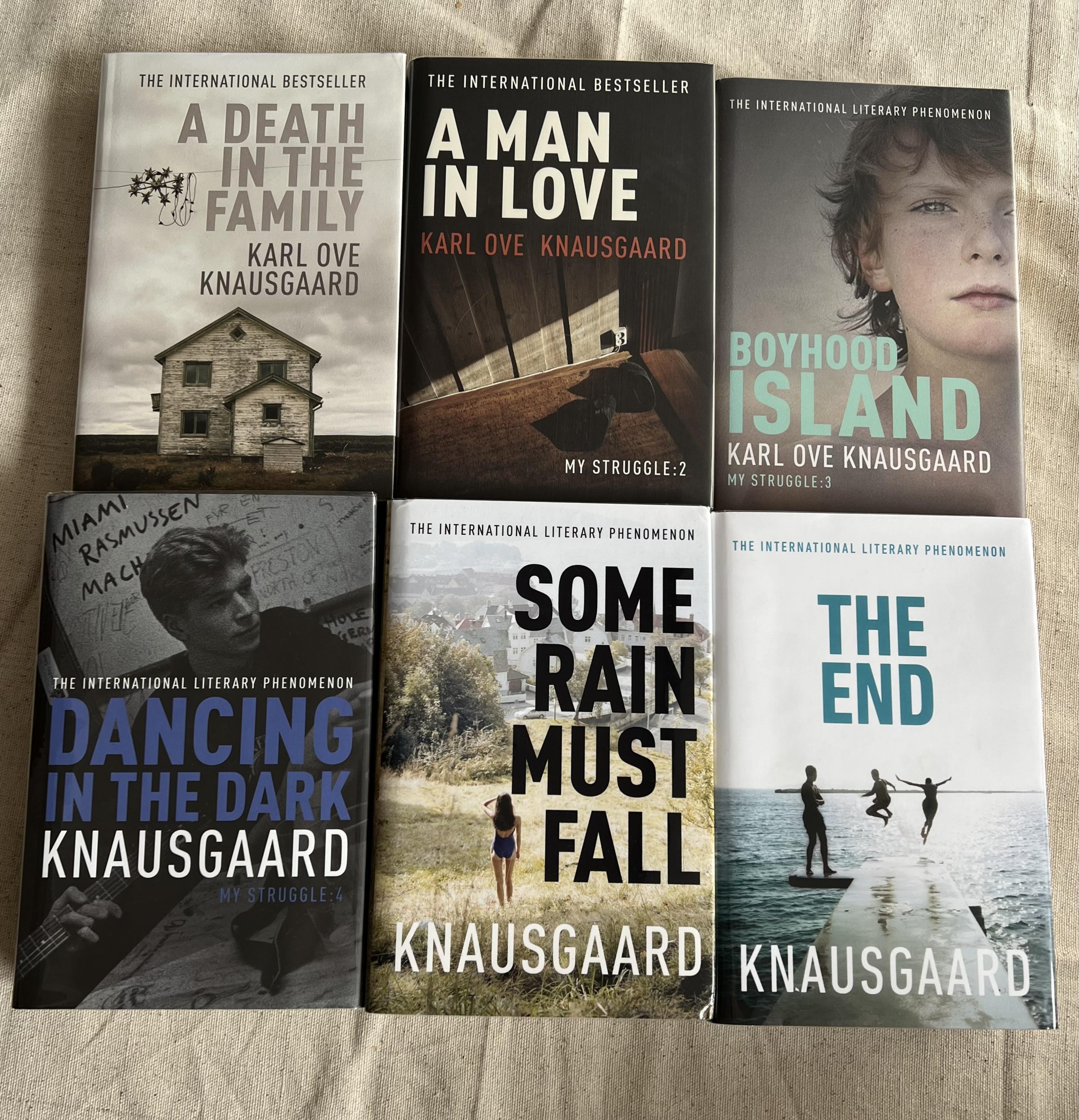

In literature too, one of the revelations of the last decade is a Norwegian writer. Karl Ove Knausgård has become a literary phenomenon with the publication of his autobiographical novel “Min Kamp (My Fight)“. Published in six volumes in Norwegian between 2009 and 2011, it has been an astounding success, with more than half a million copies of one of the titles sold in Norway, which means, one book for every nine adult inhabitants. Since then, the series has been available in 35 languages. The most demanding critics do not shy away from comparisons with Proust, Joyce or Virginia Woolf.

This summer, a strike of the airline SAS forced Céline and me to cross Norway from North to South, from the Lofoten Islands to Oslo airport, in less than twenty-four hours, 1,386 km. This long road trip was not planned, but, in the end, it did not displease us, in spite of the fatigue. We got on ferries to cross the sunny fjords, we drove mostly at night, but in early July north of the Arctic Circle the sun never sets: we could admire the arid landscapes of the national parks we crossed and see reindeers and elks at the roadside. It was probably during this marathon drive that I was inspired to start reading Knausgård’s “Min Kamp” series.

That was another long-term undertaking. In English, it is more than 3600 pages. I chose the audio-book version, superbly interpreted by Edoardo Ballerini, that is to say more than 133 hours of listening which happily accompanied me from September to February.

The radical thing about “Min Kamp” is that Knausgård tells his whole life story, at length, with details that at first sight seem trivial and banal. How he makes a cup of coffee or tea, goes out to smoke a cigarette on the balcony of his apartment and watches the neighbors, has to juggle three children and a stroller to get them to the nursery without having a nervous breakdown (and every now and then he does). When and how he meets, falls in love with, but also quarrels with Linda, his Swedish second wife (“A Man in Love”, volume 2). In the fourth volume (“Dancing in the Dark”), he tells of his experience as a young teacher just out of high school, sent to teach in a fishing village in the far north, to boys and girls barely younger than himself. Surprisingly, one is drawn into the flow of a life that is told as if live, without editing. As James Wood wrote in “The New Yorker“: “Even when I was bored, I was interested.”

The fulcrum of the novel is the relationship of the writer with his father. A difficult relationship with a father whose footsteps on the stairs he feared and who terrorized him with a look when he was a child (“Boyhood Island”, volume 3), but whom he saw decline to the point of decay in alcohol when he was a young adult (“A Death in the Family”, volume 1). It was partly the story of his relationship with his father that caused a scandal in Norway and led to his uncle suing him.

The secret of “Min Kamp” is probably that the reader recognizes himself in some of the details and habits of Karl Ove Knausgård’s life. As far as I am concerned, the Norwegian writer was born two months before me, so even though we grew up in different European countries, we have common experiences, tastes and memories. On a deeper level, the reader recognizes in this unvarnished account the movement, rhythms and, yes – the word is right – the struggle of his own life, from the most banal to the most interior.

This journey through a life, and all its range of expressions and feelings made me think of the Vigeland park-museum in Oslo. The park hosts 212 bronze and granite statues, works of the sculptor Gustav Vigeland and installed between 1940 and 1949. I had a fabulous memory of this park during my first visit to Oslo as a teenager. I went back there last July. The magic was renewed. One could spend hours observing the scenes, the movements, and the expressions of the faces of these men, women and children who play, marvel, love, argue or suffer.