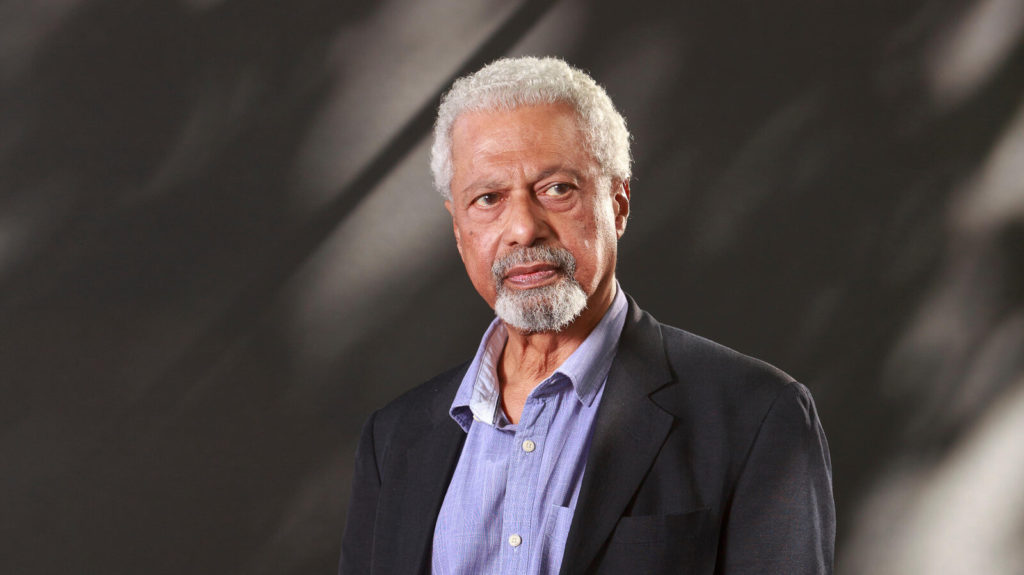

With this article, I conclude a journey that began in Zambia with Namwali Serpell and continued through Tanzania to Zanzibar, in the footsteps of Dr. Livingstone’s mortal remains, with Petina Gappah. I chose three novels by Abdulrazak Gurnah, a writer born in Zanzibar and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature in 2021, as the culmination of this journey through East Africa. I must confess to feeling a little proud when his prize was announced: few people, especially outside the English-speaking world, seemed to know this author who now lives in England. But, for my part, I had already, back in 2015, pinned one of his novels “The Last Gift” in one of my first blog posts about Tanzania.

“Paradise” is one of Gurnah’s best known novels. With a rich and precise pen, it tells the story of Yusuf, a twelve-year-old boy living on the coast of Tanzania in the early twentieth century. His father is in debt and sends his son to work for a rich Arab merchant, Aziz, who organizes caravans to the interior, to Lake Tanganyika. Yusuf participates in the journey and discovers a world that is unknown to him. The life of the villages in the heart of Africa has hardly been touched by the incursions of the English or German settlers and is nothing like what he knew on the coast. It is like the discovery of a paradise, about to be lost when it will be opened to the railroad and the exactions of the colonial administrations. Yusuf returns to the coast to the home of the man he calls Uncle Aziz. In the gardens of the rich merchant’s house, he falls in love with the young Amina. Again, a scent of the Garden of Eden, but the tender Amina is the forbidden fruit, since she is one of the wives of Aziz, his master.

“By the Sea” begins at Gatwick airport. Saleh Omar comes to seek asylum. He carries false papers in the name of Rajab Shaaban. To avoid saying anything that could compromise him, he pretends not to speak English. The official in charge of his case at the airport was surprised by the profile of this sixty-five-year-old refugee from Zanzibar. They found him a room in a small English coastal town. Since he still refused to speak English, the social services to which the refugee administration had entrusted him found an interpreter, Latif Mahmud, a professor of literature living in London. Latif, who left Zanzibar thirty years ago to study in East Germany before coming to the UK, thinks he has cut all ties with his native island. But he is intrigued by this man who seems to have usurped his father’s name. The two men meet and recognize each other. Latif dives back into the memories and buried secrets of his youth in Zanzibar: Saleh Omar is in fact the man he holds responsible for the financial and moral ruin of his family, his father having become an alcoholic, his mother collecting lovers.

With “Desertion“, Gurnak tells two stories that at first seem separate and only join their threads at the end of the novel. In 1899, in a small town on the Kenyan coast, Hassanali, on his way to the mosque at daybreak to call for prayer, comes across a man lying in the street. It was a Mzungu, a white man, thirsty and seemingly about to die. He brings him to his house so that first aid can be given to him. Soon, the colonial administrator, Turner, informed of the incident, arrived at his house to take care of his compatriot. In the process, he accused Hassanali of having robbed this traveler in perdition. After having recovered, the traveler, Martin Pearce, an English orientalist, returns at Hassanali’s place to thank the family which saved him and to ask forgiveness for the unjust accusations to which they were exposed. During this visit, Pearce falls in love with Rehana, Hassanali’s sister, whose husband has left for India and never returned.

In the second story, Amin, Rashid and Farida, two brothers and a sister, begin their adult lives in Zanzibar in the late 1950s as the colonial era comes to an end. All hopes seem to be allowed. Rashid, a brilliant student, obtains a scholarship to study in England. Absorbed by his academic ambitions, he does not pay much attention to Amin, the elder, who seems content to follow in his father’s footsteps as a teacher. Farida is a dressmaker for rich clients. One of them, Jamila, attracts Amin’s attention, despite their age difference. In the labyrinths of the old city, they manage to avoid prying eyes to see and love each other. But Amin’s parents put an abrupt end to this love. Jamila is divorced, it is rumored that she was or still is the mistress of a minister and above all, her family has a bad reputation: her grandmother had lived for several years with a white man to whom she was not married, who had then abandoned her.

These three novels are splendid and reminded me of my walks at dusk in Stone Town, the old city of Zanzibar. The setting sun gives a last ochre glow to the slightly decayed stones of the old houses, while the women with their haughty gait in their brightly colored boubous and veils return home. One wonders who is hiding behind the massive wooden doors that close and if someone is watching through the mashrabiya of the windows.