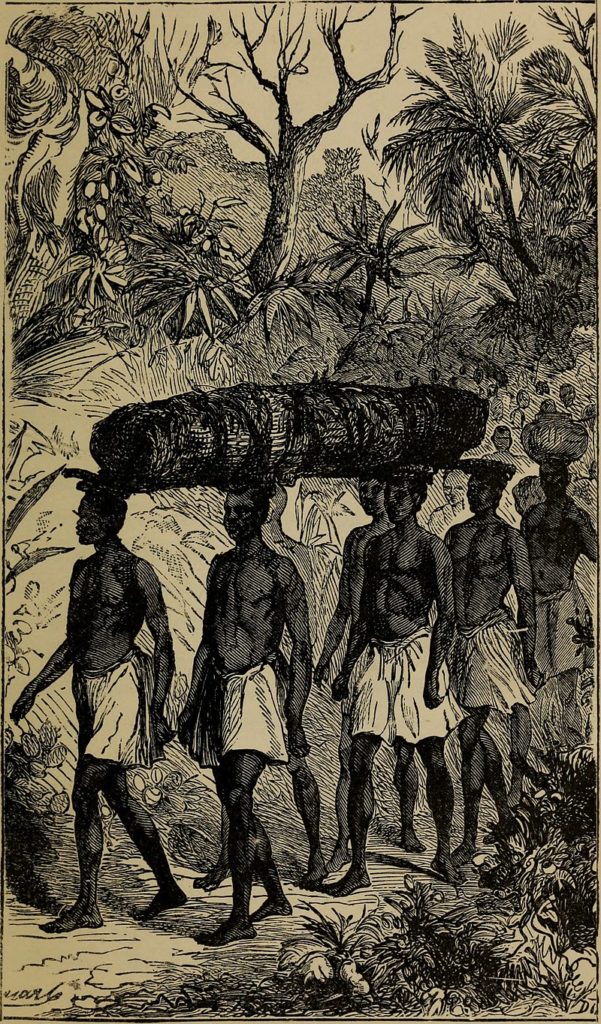

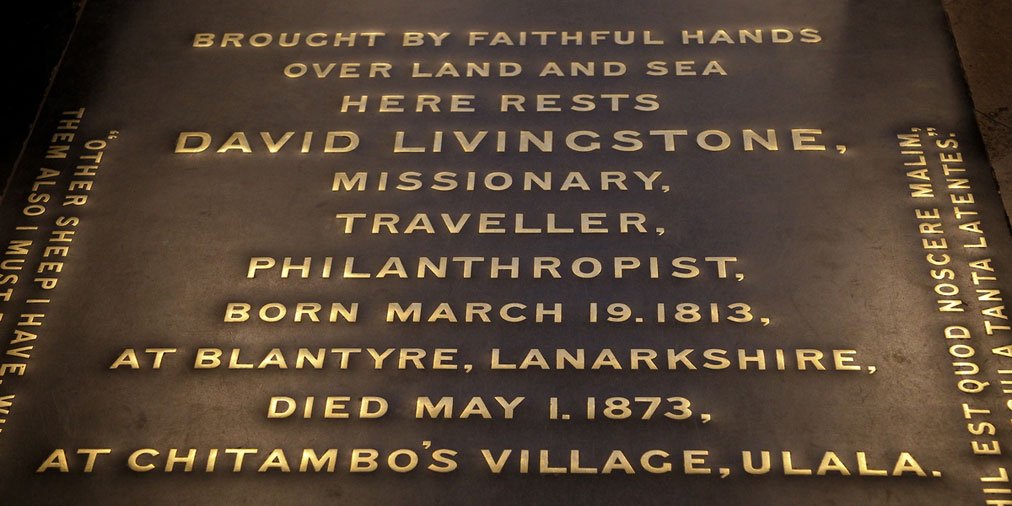

My previous article covered Zambia, including the town of Livingstone not far from Victoria Falls. Today, I invite you to take a trip that will take us from Zambia to the island of Zanzibar, off the coast of Tanzania. It is a journey that we will make following Dr. Livingstone, the famous English missionary, physician and explorer who left in search of the sources of the Nile. But it is not his trail that we will follow, but that of his servants who carried his mortal remains from the north of Zambia to the shores of the Indian Ocean so that they could be shipped back to England. David Livingstone died on May 1, 1873, in Chief Chitambo’s village, Zambia, at the age of sixty, from malaria and dysentery. His heart was buried at the foot of a tree in the village, but the rest of his body now lies in Westminster Abbey in London.

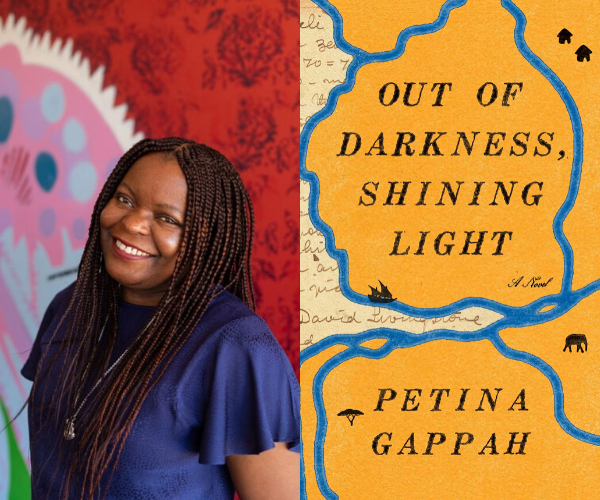

This journey of several months is the premise of Zimbabwean novelist Petina Gappah‘s superb book “Out of Darkness, Shining Light“. Her thoroughly researched novel also reverses perspectives by taking the point of view of the African servants who accompany Livingstone’s remains.

The book begins with the story of Halima, a cook whom Livingstone, though an apostle in England of the abolition of slavery, had bought on a slave market to serve as a companion to his assistant Amoda. She appears at first as a gossip who seems more interested in who of the 69 members of the expedition spends the night with whom. But she is not afraid to call a spade a spade: she cannot understand how “Bwana Daudi” abandoned his children for this madness of finding the sources of the Nile. Halima chooses to accompany this long funeral procession because she hopes to be emancipated and to settle in a house in Zanzibar.

The second voice of the novel is that of Jacob Wainwright, an African educated by Christian missionaries. He is as stiff and pompous as Halima is cheerful and cheeky. He is an Anglophile and dreams of becoming a minister. He joins the journey with the hope of meeting Livingstone’s children and gaining their support.

At the end of the novel, Halima, freed by Livingstone’s children, lives in a house with a beautiful wooden door in Zanzibar. She is respected in the city, but sometimes misses her village. Wainwright, on the other hand, has made it to London, where he was received by the explorer’s family. But when he tells the missionary society that sponsored his stay in England how the good doctor had to purchase from the slave markets to get recruits for his multiple expeditions, and how he did not hesitate to beat up the rebellious, all these nice people cringe and turn their backs on the pious Jacob who will not be ordained and whose notebooks will not be published.

This is a fascinating book, well written and which proposes a new and refreshing angle on the history of the colonization of Africa.