This Sunday is Mother’s Day. This year it falls on the same day in Belgium and in the US, which makes it easier for me, since my parents live in the former country, while my wife, the mother of my children lives in the latter. I’ve been thinking about writing an article about motherly love for some time. In fact, the idea came to me when I wrote about Notre Dame in Paris and I highlighted a passage from François Cheng’s interview: “We do not forget that it is Notre Dame, therefore a maternal presence. We know what maternal love is. For us, it is something natural, something normal. We enjoy it, we benefit from it, we often abuse it, but without worrying too much about it. One day, suddenly, this maternal presence is torn away from us. Then we are plunged into an infinite sadness, into an infinite regret. There are so many things we could have said to her and we never did. We didn’t even say “I love you”. Now it’s too late. That feeling of ‘too late’, gripped us at the very moment when the spire became a torch and collapsed.”

In the bouquet I composed for Mother’s Day, I brought together the books of three renowned French-speaking writers, a Frenchman, Romain Gary, a Swiss, Albert Cohen and a Belgian, Georges Simenon. All three are celebrated for their rich, dense or sumptuous oeuvre. They also have in common that they wrote a book dedicated to their mother. All three works were written after the death of their mother and are therefore marked by the regret and remorse evoked by François Cheng. As Albert Cohen wrote in “Book of My Mother (Le Livre de ma mère)”: “Sons of living mothers, do not forget that your mothers are mortal. I will not have written in vain, if one of you, after reading my death song, is gentler with his mother, one evening, because of me and my mother.”

The three mothers described by the three writers are, however, quite different and the relationships with their three sons are complex and sometimes difficult.

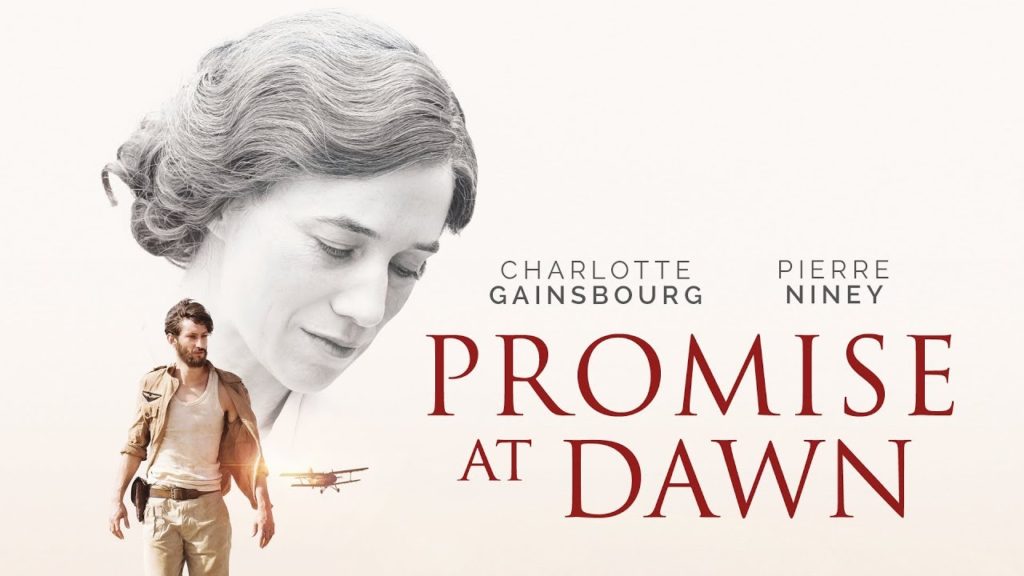

“I believe that no son has ever hated his mother as much as I did, at that moment,” writes Romain Gary, in “Promise at Dawn (La Promesse de l’Aube)”. His mother has just arrived after a five-hour cab ride on the airfield of Salon-de-Provence, where her son was then an instructor sergeant a few weeks before the beginning of World War II. In front of the mocking troop at the canteen, cane in hand and a Gauloise on her lips, she proclaims to her son: “You will be a great hero, a general, Gabriele d’Annunzio, Ambassador of France! – This rabble doesn’t know who you are!” However, the book, adapted a few years ago for the cinema, is above all a love song for this mother, who is certainly overpowering, but who has sacrificed everything for her son in whom she projects her thirst for recognition. It tells the story of the young Romain and his mother, Mina, a former actress in Moscow, a seamstress in Vilnius, before becoming a hotel manager in Nice. Her son, whom she raises alone, is her only passion, and she dreams of France as the stage for his literary, warlike and amorous exploits. Gary would fulfill many of his mother’s dreams: aviator during the war, Compagnon de la Libération, celebrated writer winning two Goncourt prizes (under two different names), husband of Jean Seberg, the American actress, muse of the New Wave Cinema, he even served as a French diplomat, he the little Jewish boy born in Poland. His mother was right and yet she would see almost none of her son’s successes: she died of stomach cancer in Nice in 1941, while Gary was serving the Free France in Africa.

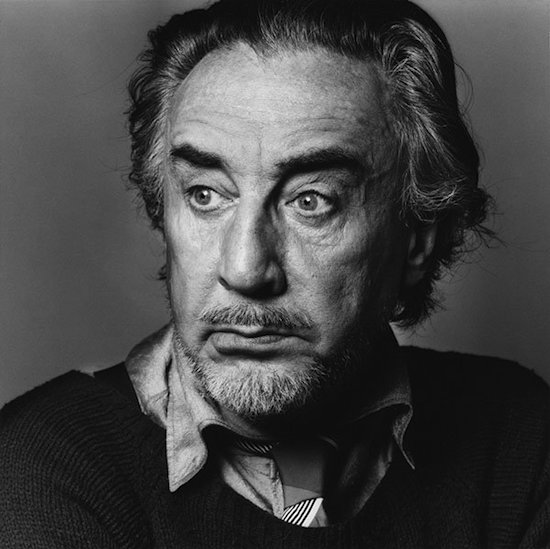

Albert Cohen also had the childhood of a young Jewish emigrant in the south of France. He was born in Corfu in 1895, but his family moved to Marseille a few years later. He observed the difficulties his parents had in integrating, the mockery, humiliation and anti-Semitism. The young Albert left Marseille in 1914 to study in Geneva. He settled there and had a career in international organizations. He only saw his mother on the rare trips he made to Marseille or more often during the regular visits she made to him. She disembarked from the train in her skimpy clothes, carrying in her arms packages full of the sweets that he loved as a child and that she still prepared for him. But he remains an ungrateful son, ignoring his mother when she is in Geneva, to run after some elegant woman, with whom he will never find the same unconditional love: “All the other women have their dear little autonomous self, their life, their thirst for personal happiness, their sleep which they protect and beware of who touches it. My mother had no self, but a son.” Albert Cohen was in London when his mother died in 1943 in Marseille. In 1954, he wrote “Book of My Mother (Le livre de ma mère)”, a sumptuous – some would say grandiloquent – literary monument to his mother’s love. But a monument inspired by guilt. During an interview, he said:

“This book, I wrote it to avenge my mother.

– Revenge for what?

– For her son.”

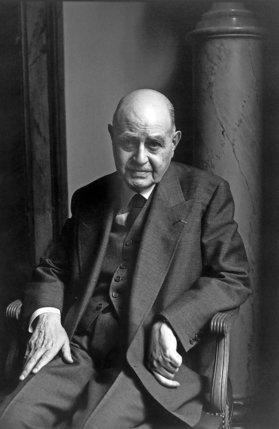

With “Letter to My Mother (Lettre à ma mère)” by Georges Simenon, we are at the antipodes of the loving mother, too loving no doubt, of Gary and Cohen. When Simenon learns that his mother is hospitalized at the Bavière Hospital in Liège, he makes the trip from Lausanne where he lives. When she saw him enter the room, she asked “Why did you come, Georges? The writer spent several days at the bedside of his dying mother. He begins by recalling his childhood, which he had already mentioned in “Pedigree“, and how his mother was always afraid that he would do extravagant things in his job as a journalist and then as a writer. She was content with the “bare necessities” in her house in the working-class district of Outremeuse and could never believe that he could live from the sale of his novels. She asked his wife if they were not in debt because of the purchase of their property in Lausanne. She kept all the money he had sent her, before returning it, to the nearest franc. He also remembers that she preferred Christian, her younger brother, to him. After the death of the latter around age 40, his mother said without blinking: “How unfortunate, Georges, that it is Christian who died.”

Simenon will never forget this sentence, but little by little in this “Letter to my mother” he tries to understand her. Henriette Brüll is the last daughter of a family of thirteen, whose alcoholic father died when she was five. Her family is in need, and she is taken in by her sister who has married a successful grocer. But young Henriette is treated as a maid who eats at the servants’ table. Then she worked as a saleswoman at the department store “L’Innovation” where she met the handsome Désiré Simenon, who brought her a stability, admittedly narrow, but which she stubbornly wanted to preserve from any upheaval. The relationship between Simenon and his mother was difficult, and he suffered from this lack of love. And yet this book, which he wrote three and a half years after her death and which he begins with “Ma chère maman”, whereas all his life he had to call her “mother (mère)”, can also be read as an attempt to show his love for her.

These three books I’ve gathered for Mother’s Day are moving because, although in very different styles, they are all written with sincerity and they remind us, as Romain Gary writes, in a sentence that announces its title, “With motherly love, life makes you a promise at dawn that it can never hold.”

Credit for featured photo: Mahmud, Bangladesh