China remains a difficult world to understand and decode. The language barrier makes even the most fascinating journeys seem to touch only the surface. This same barrier also limits the access to Chinese literature. In a previous article, I described “Wild Swans” by Jung Chang, written in English and masterfully recounting the lives of three generations of women, from imperial China to the modern period, through the turmoil of the revolution.

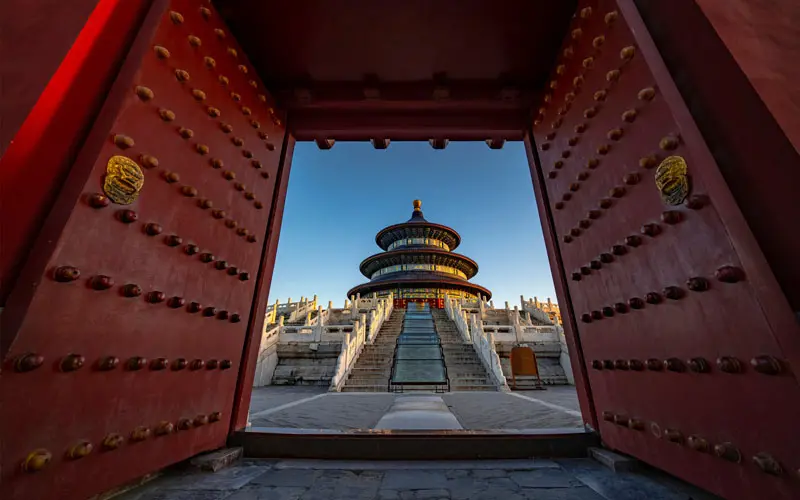

I recently enjoyed reading two novels by Chinese writers. The first one, “Little Gods” is written by Meng Jin, a young writer born in Shanghai but living in the United States. The heart of the novel is the relationship between a mother and her daughter. The mother, Su Lan, gives birth to her daughter, Liya, in a Beijing hospital during the events in Tiananmen Square, while the wounded are pouring into the emergency room. She had gone up from Shanghai to Beijing to find her husband who was attracted by the political changes in the capital. She will lose track of him and will end up having to raise her daughter alone. As she is a brilliant student, she obtains a scholarship to study physics in the United States. Mother and daughter emigrated when Liya was two years old. But Su Lan did not manage to complete her doctoral studies and proved to be a distant mother.

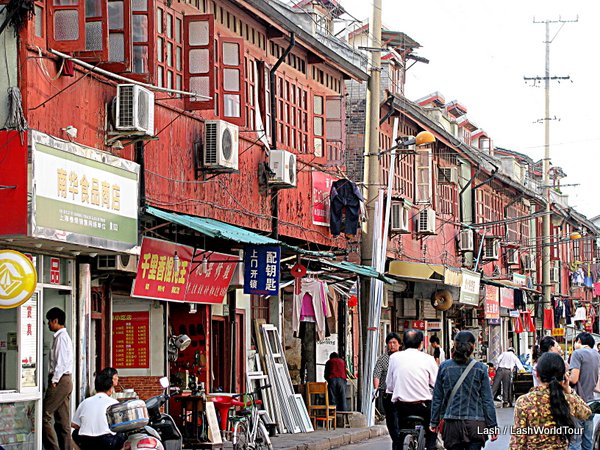

When she dies, her daughter returns to Shanghai, seventeen years later, to better understand the mystery that was her mother. The novel gives us a glimpse of Su Lan’s character from three perspectives: that of Liya, the daughter, that of the missing husband, and that of Zhu Weng, a woman who had helped the young mother raise her daughter when she returned to Shanghai, in an old neighborhood that is on the verge of demolition when Liya returns to China. It is a complex and fascinating book that underlines how difficult it is to grasp the different facets of a human existence, this amalgam anchored in the past but looking towards the future.

The second novel is “Decoded” by Mai Jia, the pseudonym of a former member of the armed forces who probably worked for the secret service, who has now become a very popular author in China. This is the first of his books to be translated from Chinese. The story begins in the late 19th century with the Rong family, a family of salt merchants in southern China. One of the children is sent to study mathematics at Cambridge. The family begins to turn to the scholarly world, holding several prestigious academic positions. But it was not spared tragedy, with several mothers dying in childbirth.

Born in the early 1930s, Jinzhen was an illegitimate offspring who also “killed” his mother at birth because his head was too large. He is neglected by the whole family, but is taken in by Mr. Auslander, a European, who lives in their domain and discovers then encourages his extraordinary gift for numbers and convinces the head of the family to reintegrate him and to finance his studies. At the university he became the disciple of a Polish Jewish professor, Jan Liseiwicz, who introduced him to mathematics at the most advanced level. But very quickly, the pupil exceeds the master, until an official of the Communist Party comes in 1956 to poach him almost by force to work within the very secret unit 701. Rong Jinzhen becomes a hero when he deciphers the secret codes of an enemy country, only to fail in his next challenge. Although the book has been described as a spy novel, it is not a thriller. Rather, it is a reflection on the sometimes fragile line between genius and madness.