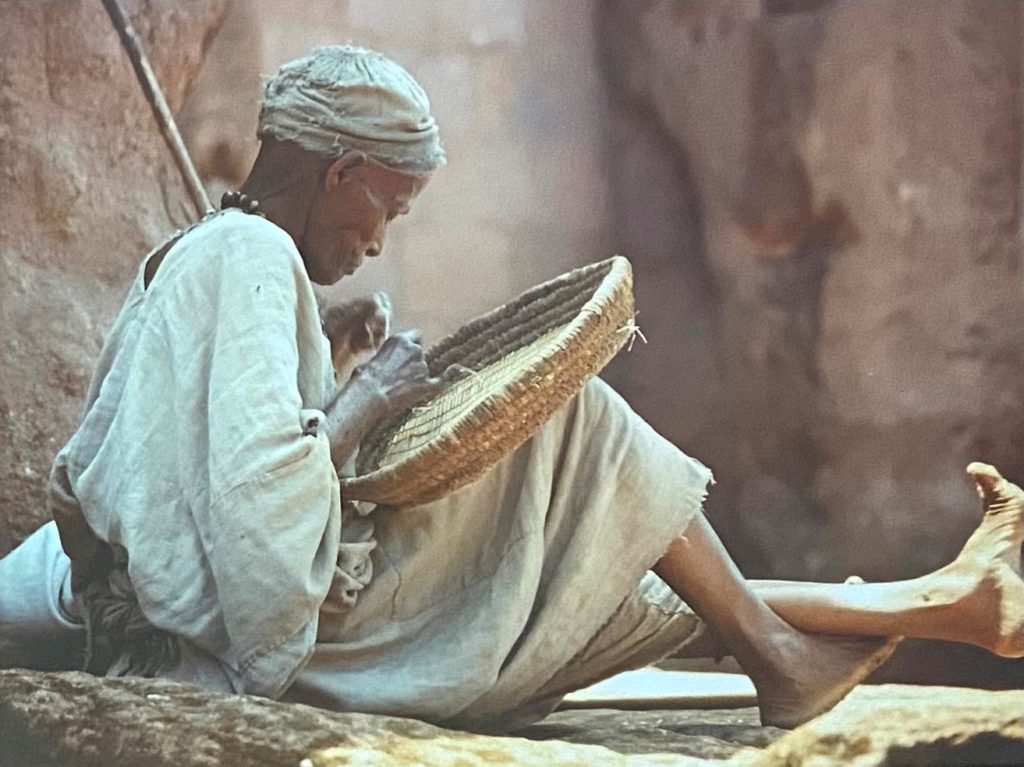

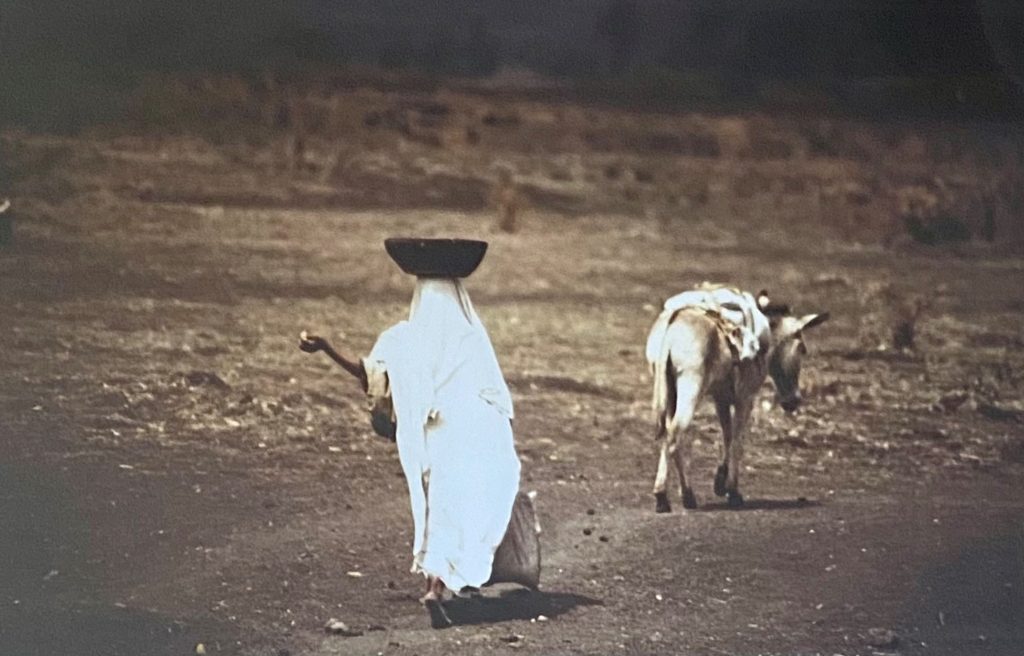

We have several photographs from Ethiopia in our living room. There are four enlargements of pictures my wife Céline took during our trip in 1995. Superb views of the Simien mountains in which we had trekked for 3-4 days, going through villages before climbing to the plateau dotted with a few shepherds’ huts. A few minutes by foot were enough to reach the edge and admire the blue, white and browns tones of the canyons streaking an immense valley.

We also framed black-and-white photos dating from the Spring of 1934 when a great-great-uncle travelled for an official mission from Djibouti to Addis-Ababa. Men with turbans beat on large drums. Women walk in procession protected from the sun by embroidered umbrellas. The two shots have likely been taken during a religious festival. I do not have more details.

My interest for these pictures was renewed when reading « The Shadow King », the beautiful novel by Ethiopian writer Maaza Mengiste. The story takes place in 1935 during the invasion of Ethiopia by Mussolini’s Italian army. A great deal of the action is set in and around the Simien mountains and the photographs taken by Ettore, an Italian soldier are part of the book’s plot. Maaza Mengiste conducted extensive research, partly in Italy, to find period photos and set up a photographic archive project of the 1935-1941 Italo-Ethiopian War.

The shadow king in the novel is a peasant who looked very much like the Emperor Haile Selassie. He was dressed in an imperial uniform and paraded on a horse on the hill crests to give renewed courage to the Ethiopian soldiers while the actual Negus lived in exile in Bath in England.

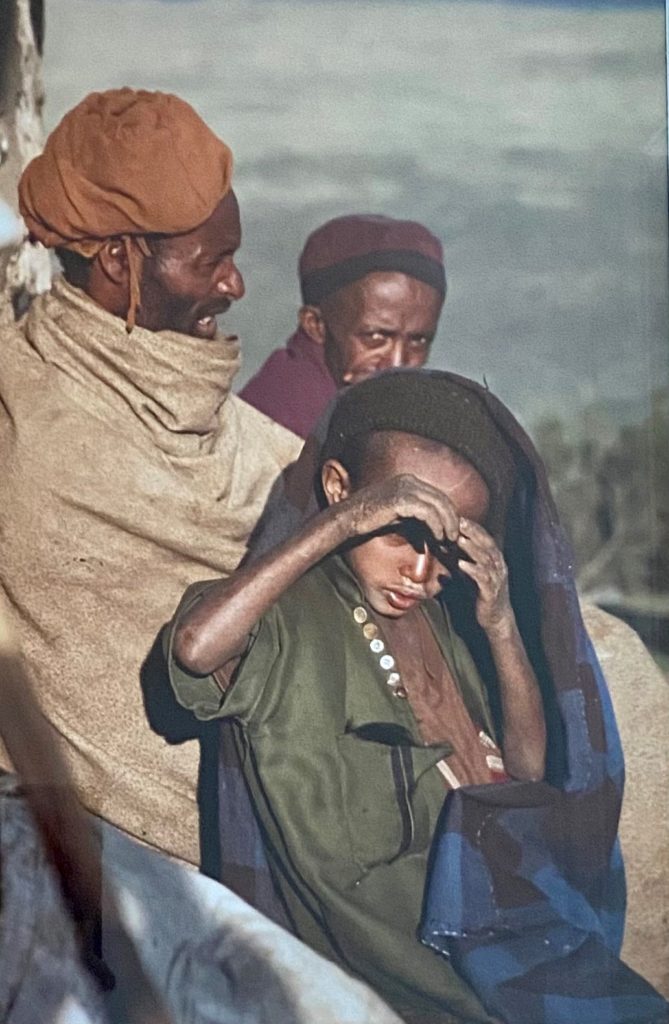

One of the Shadow King’s bodyguards is Hirut, the book’s central figure. She first appears as a young maid, humiliated by Aster, her mistress, who is jealous of the attention she gets from Kidane, her husband. Kidane is a leader in the Ethiopian army. When the battle starts, he wants to leave the two women behind, but they insist to join the combats. One of the novel’s strengths is how it shows the war through the eyes of the women. That’s why it remembered me of « The Unwomanly Face of War », the work by Byelorussian writer Svetlana Alexievitch gathering testimonies from women enlisted in the Red Army during World War II.

Maaza Mengiste ‘s novel, very well written and composed, is also an admirable effort to understand this war both from the Ethiopian and the Italian point of views. This effort relied on research made by the author to find period photographs on flea markets in Italian cities. Doing so, she met many soldiers’ relatives. And indeed, the story follows Hirut’s itinerary, but also Ettore’s experience. He is a soldier from Venice, always a camera strapped around his shoulders, disembarking in Asmara in an Africa unknown to him, taking exotic clichés, before being forced by his colonel to immortalize the execution of Ethiopian prisoners pushed from a cliff. It is in this prisoners’ camp that he will meet Hirut and take her picture, before finding her back in Addis-Ababa’s railway station in 1974, as Haile Selassie’s regime was crumbling.