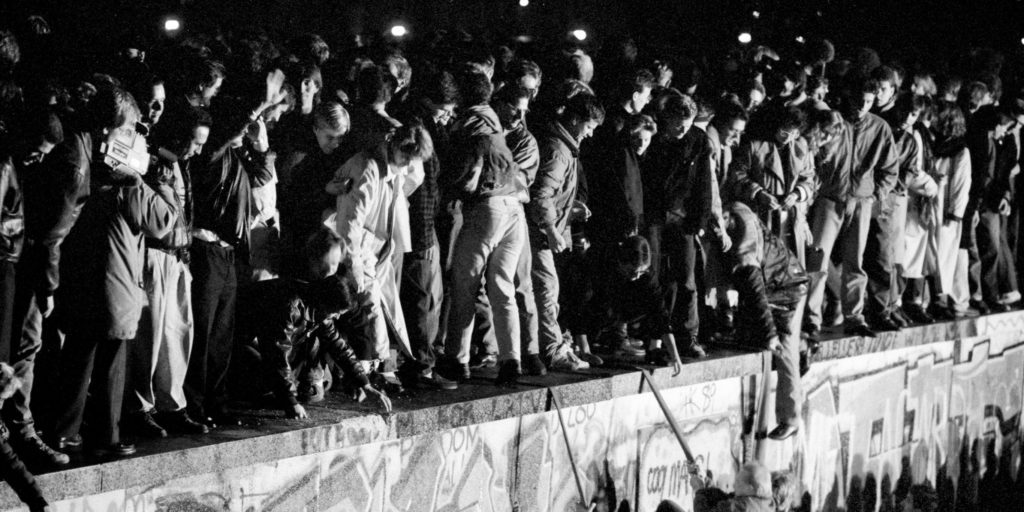

We arrived in Berlin on Saturday November 11, 1989. The Wall fell on the night of Thursday the 9th. You will kindly notice that I more accurate in my memories than President Nicolas Sarkozy.

I was 20 years old and with my brother and a group of friends we had left Brussels in the middle of the night, on the spur of the moment, to join the celebrating crowds and partake in that event marking the end of the Cold War and of Europe’s division. We had brought pickaxes in our cars’ trunks and brandished them to hit the Wall. We lent them around us, they circulated and then disappeared. I still have somewhere in my parents’ attic some graffiti-covered pieces of that Wall that we wanted to smash. We crossed from West to East and came back through one of the openings in the Wall, welcomed with Sekt and cakes as if we were Ossis arriving to discover the other side. After trying without much success to explain that we were just visitors, we played along. We almost ended up being interviewed by a French TV crew, before disabusing them by answering in French.

Since then I went back several times to that city that I like very much. But of course, it is this first trip that was the most memorable. It was intoxicating to get carried away for a week-end by the wind of history blowing on Berlin and Europe. For the last century history made frequent stops in Belin, not all of them as happy as in 1989. I propose five books as a basis for a tour of the history of the German capital.

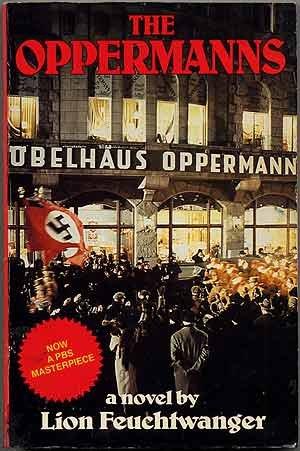

« The Oppermans » is a novel that tells the story of three brothers from the Jewish haute bourgeoisie in Berlin, heirs to a famous furniture factory. Gustav Opperman, the elder, is a dilettante scholar, his brother Martin manages the family company and Edgar, the cadet, is a renowned medical specialist. The book’s first part, entitled « yesterday », is set in November 1932 and the three brothers are still at the peak of their influence in their respective circles. The second part (« today ») details how, starting in the beginning of 1933, the joint rise of Nazism and antisemitism progressively affects them and finally upends their lives : the factory is cheated by a competitor who in the past was not even a threat; Berthold, Martin’s son, is expelled from his soccer club, persecuted by one his professors at school and ends up taking his life while Edgar becomes the victim of calumny as he is accused of killing his patients. The last part (« tomorrow ») focuses on Gustav’s exile in Switzerland and then France. The novel admirably describes how totalitarianism and persecution insinuates themselves without warning, insidiously, to the point that the victims only recognize their signs and risks too late. What is fascinating is that this book was not written with the benefit of historical perspective. It was written and published in 1933 by Lion Feuchtwanger a Jewish writer from Berlin who himself was forced in exile that same year and whose publications would be burned during the Nazis.

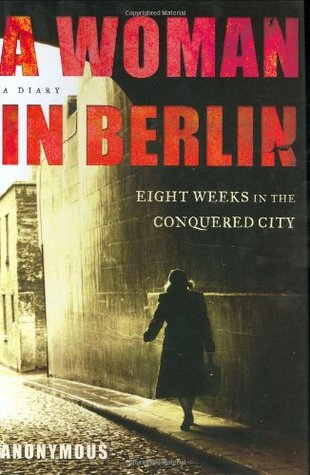

« A Woman in Berlin (Eine Frau in Berlin) » brings us to the bitter end of the Nazi tragedy. It is the journal written by a young woman between April 20 and June 22, 1945, as Hitler’s regime falls apart and the city is under siege, conquered and then occupied by the Red Army. The author wanted to remain anonymous, but her identity was later unveiled. She describes the privations, the struggle to find something to survive on, the rapes by the Soviet soldiers and the need to find a « protector » among the officers in the occupying army. Her account is thorough, and she shows an impressive restraint, sometimes even irony, given the violence she encountered. As if keeping this journal had allowed her to find a refuge. The book was first published in 1954 in English and then in the original German text in 1959. At the time it was very poorly received in Germany where the emotions and taboos were still too raw. Since then, it has been recognized as a crucial testimony about this dramatic period in history and women’s experiences in war’s turmoil. The book has been adapted for the cinema, but I haven’t yet watched the movie.

Peter Schneider wrote « The Wall Jumper (The Mauerspringer) » in 1982, when the Berlin Wall, erected in 1961 was still standing. Through a series of short tableaux, he sketches the picture of a divided city. The narrator is a writer from the West who travels to the East, at first almost by accident, and then more often as he gets interested by the life on the other side of the Wall. He befriends people from East Berlin, Robert and Lena who passed to the West and Pommerer who remained in the East. He also tells the story of teenagers from the East managing to come to the West to watch westerns in the movie theaters on the Kurfürstendamm before returning on the other the side of the Wall. Finally, he describes how the city’s divisions go beyond the physical barrier imposed by the Wall: ”It will take us longer to tear down the Wall in our heads than any wrecking company will need for the Wall we can see.”

« Surrogate City » is the first novel written by the Irish writer Hugo Hamilton who lived for a long time in Berlin. It was published in 1990, just after the fall of the Wall, but this story in which human relationships appear as distant and temporary is set in the 70s. Helen, an Irish girl, met a German, Dieter in Dublin. She doesn’t know much about him, except that he left her pregnant. She arrives in Berlin to try to find him and tell him that he will become a father. But she has a hard time finding Dieter who seems elusive and Helen is welcomed by Hadja, the wife and manager of Wolf, a popular musician. The narrator, also from Ireland, is Wolf’s sound engineer. He gets to know Helen and helps her searching for Dieter. But he remains impossible to find. The sound engineer falls in love with Helen and offers himself as surrogate father. Until Dieter reappears and takes Helen to Ireland.

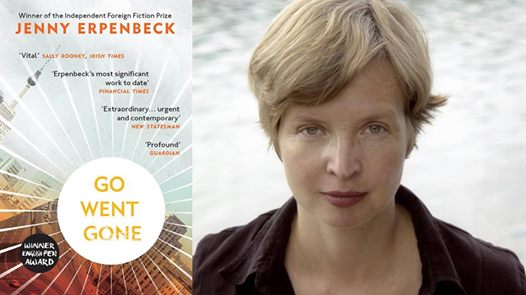

The last novel in my Berlin trip « Go, Went, Gone (Gehen, Ging, Gegangen) » is by Jenny Erpenbeck, a writer born in East Berlin. It covers the contemporary period since it is about the refugee crisis in Germany but at the same time it allows a flash back towards Berlin’s history. Richard is a retired scholar who by happenstance discovers on the famous Alexanderplatz the tents sheltering refugees from Africa and Asia who are threatened by expulsion. He gets interested by their case, first like an academic would approach a new research topic: with careful distance. When the refugees are transferred to an old nursing home in Spandau, Richard follows them, befriends some of them, tries to help them, sometimes clumsily, and invites a few of them to his house. This leads to funny scenes between two generations and two worlds poorly equipped to understand each other. But the novel goes beyond this very delicate description of culture shocks. Richard was just a child at the end of the war, but he experienced the exile roads from Silesia to Berlin as the Soviet troops were advancing and during that exodus he was almost lost by his mother. His father served in the Wehrmacht. He accomplished his entire academic career in an East-Berlin university, confined behind the Wall. In the end, this novel written with a lot of tact is as much a book about the lives of refugees as a reflection about Richard’s life, and through him, about Berlin’s history.