I have just read with a lot of pleasure two books by French novelists which trace back immigration itineraries by families, from their origins in Algeria and Iran respectively, until the arrival in France and the integration of the migrants and their children. I had previously discussed four novels about African immigrant experiences in the US. Beyond the arrival destination, one difference I noted, is that these two novels take place over several generations and therefore underscore how integration can only occur after a long period of time.

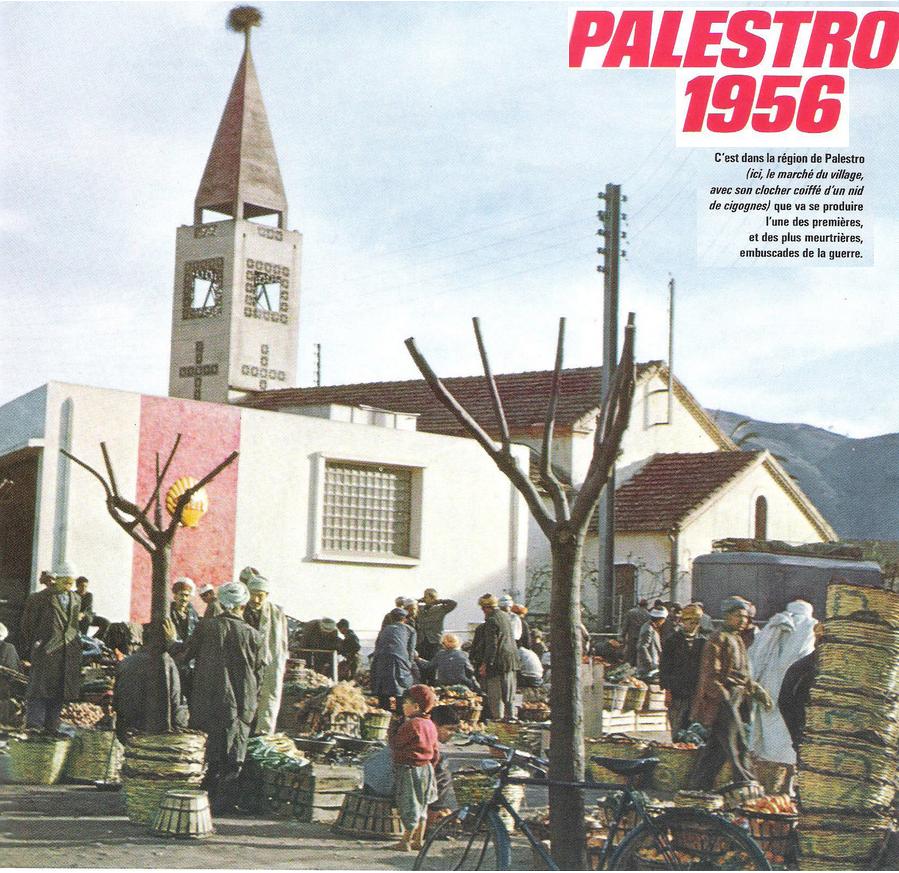

In « L’Art de Perdre » (« The Art of Losing », not yet translated in English), Alice Zeniter gives voice to the « harkis » and their history. « Harki » is the name given to Algerians who, by explicit choice or not, took the French side during the Independence War. Ali, the grand-father, was a leader in his village in Kabylie where he was producing olive oil. He had served in the French army at the battle of Monte Cassino during World War II. He came back with a medal and enjoyed meeting the veterans in the local of their association in Palestro (now Lakhdaria). When the conflict with the Independentists from FLN got closer to his village, he served as intermediary with the French officers. After the Independence in 1962, he would be marked as a traitor. He managed to escape with his family and to cross the Mediterranean.

After many years in refugee camps in Southern France, he finds a factory job and a flat in the projects further North. His prestige as a father is gone, he rarely speaks and his son Hamid takes his distances: after his studies, he moves up to Paris, get married with Clarisse, a French woman, and doesn’t want to hear any more about Algeria. It is Naïma, one of Hamid’ daughters, who works in a fashionable art gallery in Paris, who will, a little by chance, get to reconnect the threads of the family itinerary. As the grand-daughter of harkis, she takes advantage of a trip to set up an exhibition about an Algerian artist and decides to visit the Kabyle village of their origins. It is a very nice book which fills with patience the blanks in a family history – and even in history itself – in which silence was transmitted from generation to generation.

« Disoriental (Désorientale) » by Négar Djavadi announces its theme in its title. It is also a journey from the Orient to the Occident to which this novel invites us, as well as an itinerary over four generations. Kimiâ, the narrator, is in the waiting room of a medically-assisted procreation center, with Pierre, a friend who accepted to be the pretend father so that she could have a baby with Anna, her partner. But in this novel which is not constructed as linearly as Alice Zeniter’s book, she also sends the reader, by small fragments, to the Iran of her great-grand-father, a landlord in the mountains along the Caspian Sea who had his own harem. Kimiâ describes the role played by her father, Darius Sadr, an intellectual and opponent to the Shah who joyfully welcomed the 1979 Revolution, before quickly becoming disenchanted and opposing Khomeini. And she tells the story of her mother, Sara, who clandestinely crossed with her daughters the border between Iran and Turkey to join her husband who had to escape to Paris to avoid being arrested by the Guardians of the Revolution. Paris was a dream city for these intellectuals from Teheran’s “grande bourgeoisie”, but they arrive as penniless exiles.

Kimiâ, born in Teheran, lands in France just before becoming a teenager. She needs to find her way between her omnipresent mother and the much-revered fatherly figure. While doing this, through escapades and discoveries in Brussels and Amsterdam, she step-by-step leaves the oriental mold of the family lived as a community, a mold in which her mother and her two grand-mothers had agreed to melt. She finds herself, somewhat disoriented, facing her individual destiny as a woman, planning to conceive a child inside the cold walls of a clinic.