When I took advantage of a free Saturday between two work weeks in Ghana to explore Elmina and Cape Coast, on the coast west of Accra, I was surprised by the amount and the size of the funerals I could see from the road or in the towns. Saturday is funeral’s day in Ghana and our driver explained that this was Ghanaians’ favorite pastime on that day of the week. Several times on the road we were slowed down by burial processions, with men and women all in back, sometimes crying, sometimes singing, sometimes dancing. In Cape Coast Castle’s courtyard – an important slave trade memorial- large groups of women clad in black and white dresses followed a guided tour before going to a funeral.

A few days later, intrigued by this place given to funeral rites, I woke up early and took a taxi from my hotel on Labadie Beach in Accra until the peri-urban village of Teshie a few miles to the East on the ocean. I had read that it was possible to see one of the workshops making fantasy coffins. It was just 7am, but the carpenters were already at work. I was amazed in discovering all these coffins made to order and personalized to illustrate the life – their profession, their passion or their character – of the deceased. I saw in the workshop’s display on the road or in the back rooms, every which way, finished or in construction, a piano, a Ghana Airways plane, several different cars, fishes, cocoa beans, a beer bottle, a movie projector with its reel, a leopard, a carpenter’s plane, a hammer, a wrench… Each of these wooden sculptures, painted in bright colors, could be opened from the top to reveal a box padded with velvet in which the corpse would eventually take place. While I was taking a few of the pictures accompanying this post, I was trying to imagine the activity or the personality of those who would soon be buried in these art works which by definition are bound to be ephemeral.

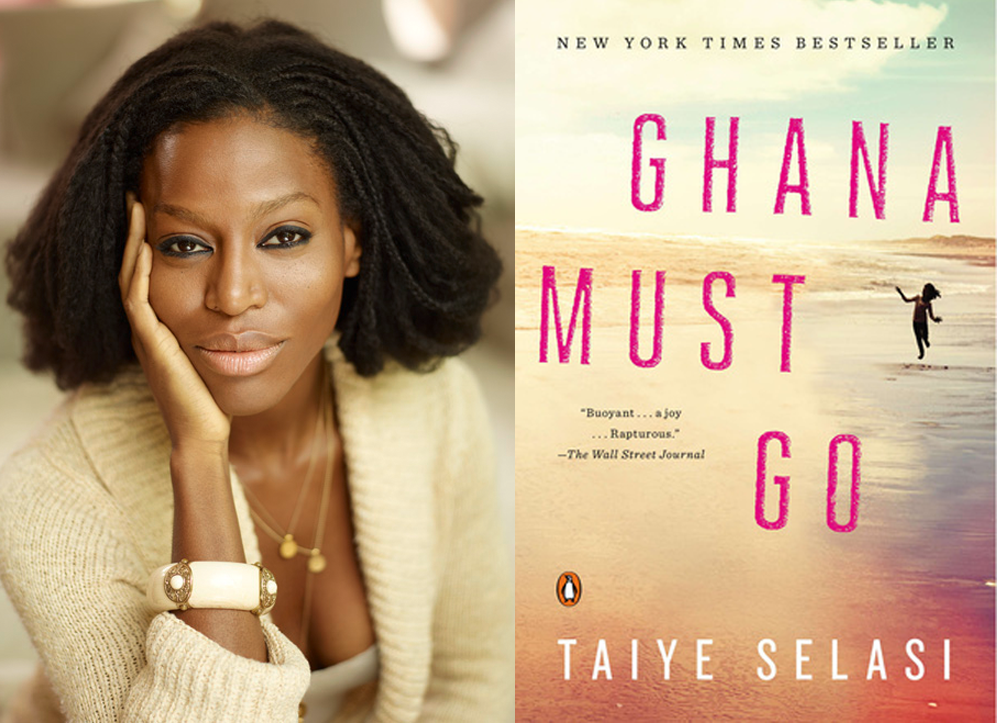

Taiye Selasi’s novel «Ghana Must Go » is built around a Ghanaian funeral. Kweku Sai’s first wife and four children actually visit a fantasy coffin workshop before opting for cremation and letting the ocean take away the urn containing their husband and father’s ashes. Kweku grew up in that small fishermen’s village on the coast. A brilliant student, he had managed to immigrate to the US to study and become a renowned surgeon in one of Boston’s prestigious hospitals. That’s where he would meet and marry Fola, a Nigerian woman, and where, as a perfect picture of the American dream, they would raise their four children: Olu, Taiwo and Kehinde, the twins, and Sadie. Following an unfounded accusation of medical malpractice, he decides without any warning to leave the US and abandon his family. He goes back living in Ghana, marries one of his nurses, and one morning, victim of a cardiac arrest that he probably could have stopped, he dies laying in the still humid grass of his courtyard with a view on the sea.

Taiye Selasi gave a very popular TED talk where she suggests not to ask people from which country they come from but rather in which cities or even neighborhood they are locals. She also contributed to popularize the concept of “Afropolitans”, those Africans who moved a lot in their lives and are at ease on several continents. Her book describes each member of this Afropolitan family when they learn about Kweku’s passing. Since their father return to Ghana, each tried as best as they could to grow up and find their way. Olu, the perfect son, walked in his father’s footsteps becoming a promising surgeon in the US. He married Ling, another doctor, the daughter of Chinese immigrants. After a few traumatic months in Nigeria where their mother had send them to continue high school under the supervision of her half-brother, the twins who had always been very fusional have a hard time talking to each other. Taiwo is an excellent student but in law school in New-York she falls in love with the Dean. Their affair becomes a scandal and she drops out. Kehinde is now an up and coming artist, but his arms bear the traces of the day when he tried to open his veins. Sadie, the youngest, remained for long her mother Fola’s « baby » before breaking-up with her as she was getting into Yale. This pushed Fola to also settle in Ghana, without however re-contacting her ex-husband.

The four children and Ling take the same flight from New-York and Fola welcomes them at Accra airport. While preparing the funeral, they talk, share their secrets and disappointments and leave their fears. I really enjoyed this novel even though it took me a little bit of time to “get into it”. Even if the book is about immigration and the feeling of living across two cultures, I also liked it beyond this perspective. First and foremost, it is the story of a family, its hopes and its bonds, its break-ups and itineraries. A family who gets together one morning for a funeral – very sober by Ghanaian standards – next to the ocean.

NB: The title « Ghana Must Go » refers to the expulsion of Ghanaian immigrants from Nigeria in 1983. This name was given to the large shapeless but colorful plastic bags in which the refugees took whatever they could. “Ghana Must Go” bags are still often seen on the luggage carousels of many airports and they have recently become somewhat fashionable. One of these bags appear in the novel’s last pages.