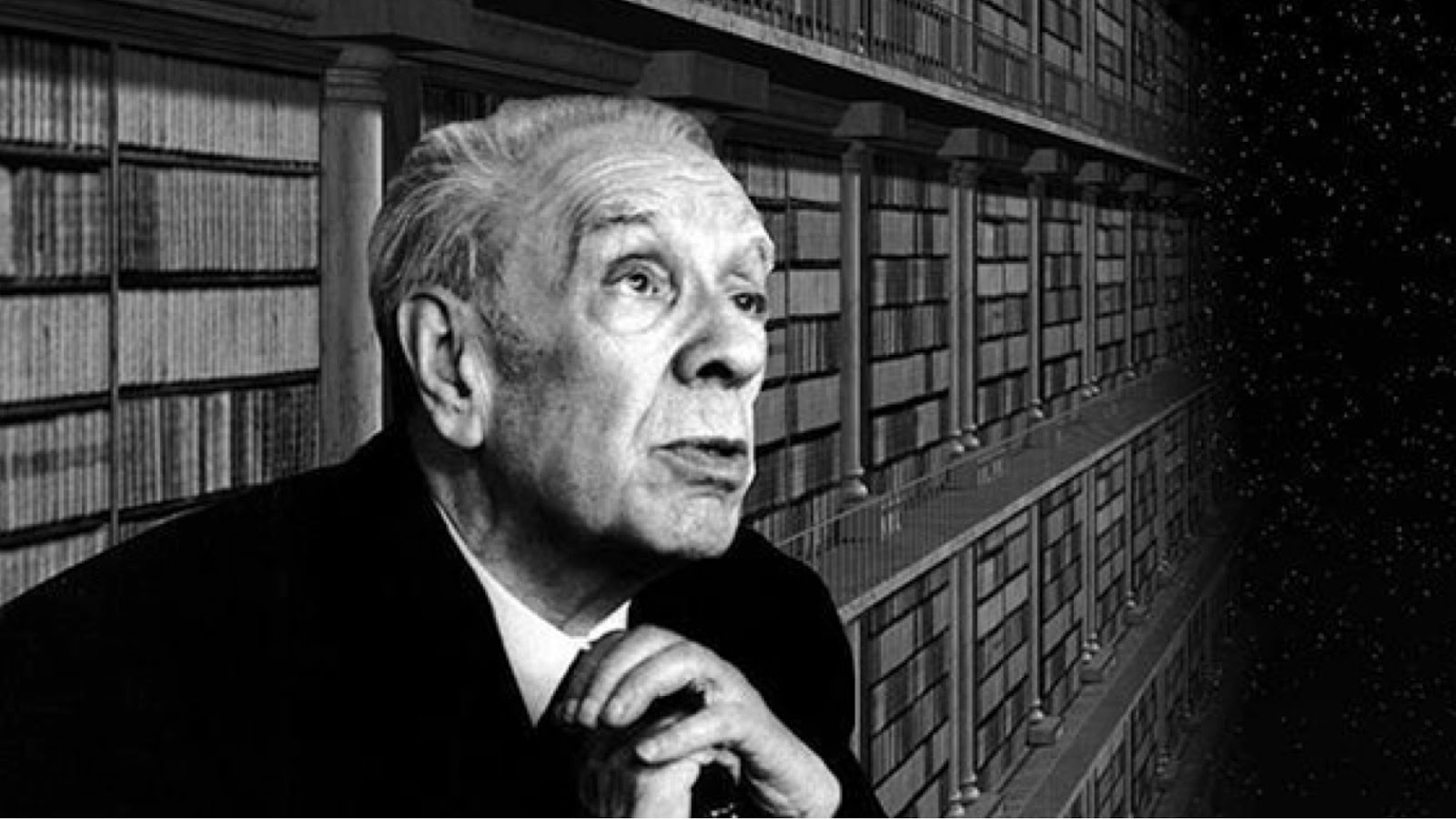

The first time I heard about Jorge Luis Borges, it was many years ago while reading “The Name of the Rose” by Umberto Eco. The Argentinian writer was the inspiration behind the character of Jorge of Burgos, the old blind monk, curator of the ancient library and the guardian of all sources of knowledge.

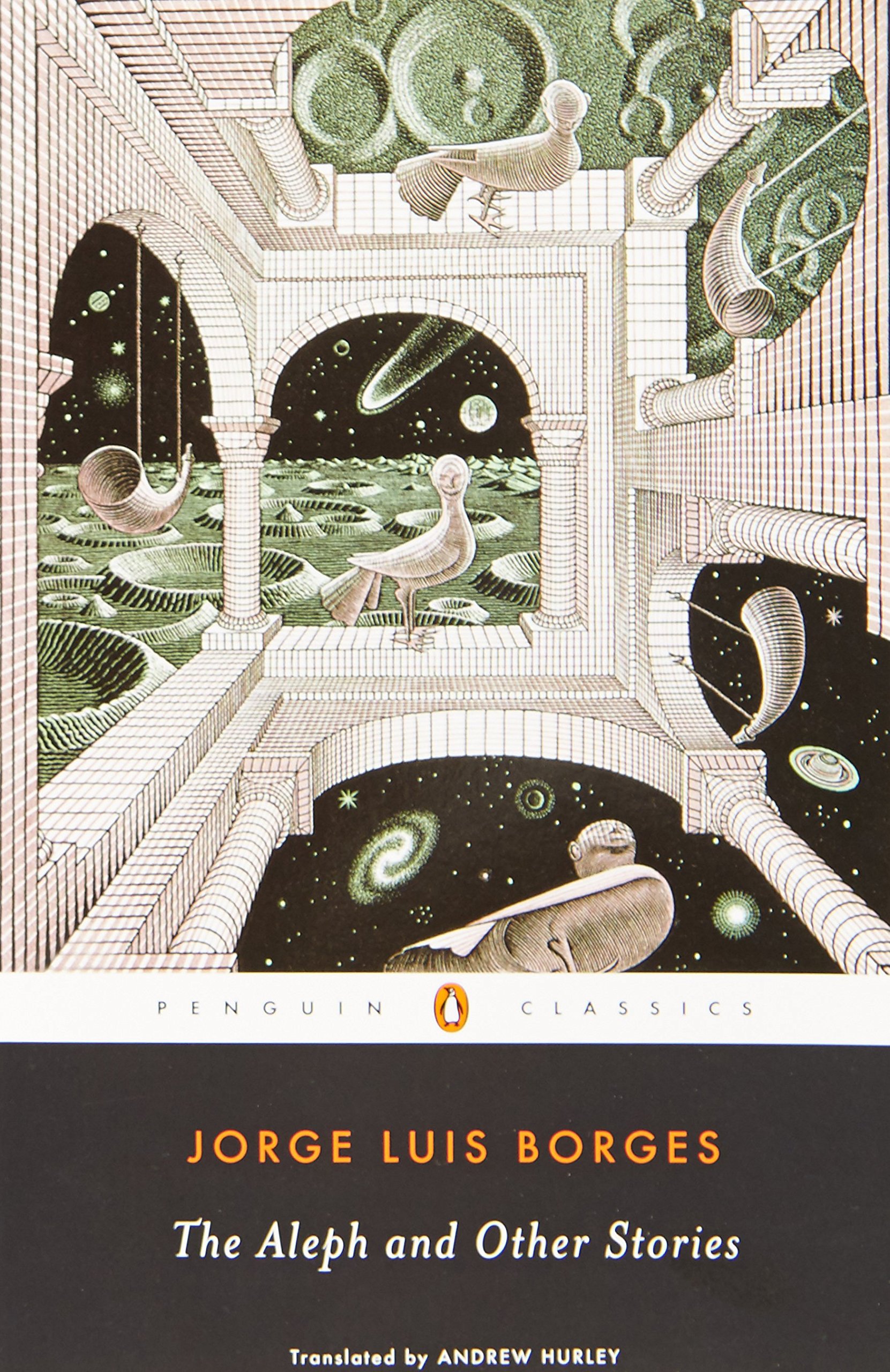

I waited until my first trip to Buenos Aires to read some of his work, and in particular his short stories collections « Fictions (Ficciones) » and « The Aleph (El Aleph) ». I also visited the old National Library, currently the Centro Nacional de la Música, where Borges was the director. It also seems that it is there that Umberto Eco met the famous librarian. « The Library of Babel », a short story in « Fictions » is most probably the inspiration for the one in the « Name of the Rose »,’s abbey. Some have also seen it as an anticipated version of internet and the worldwide web.

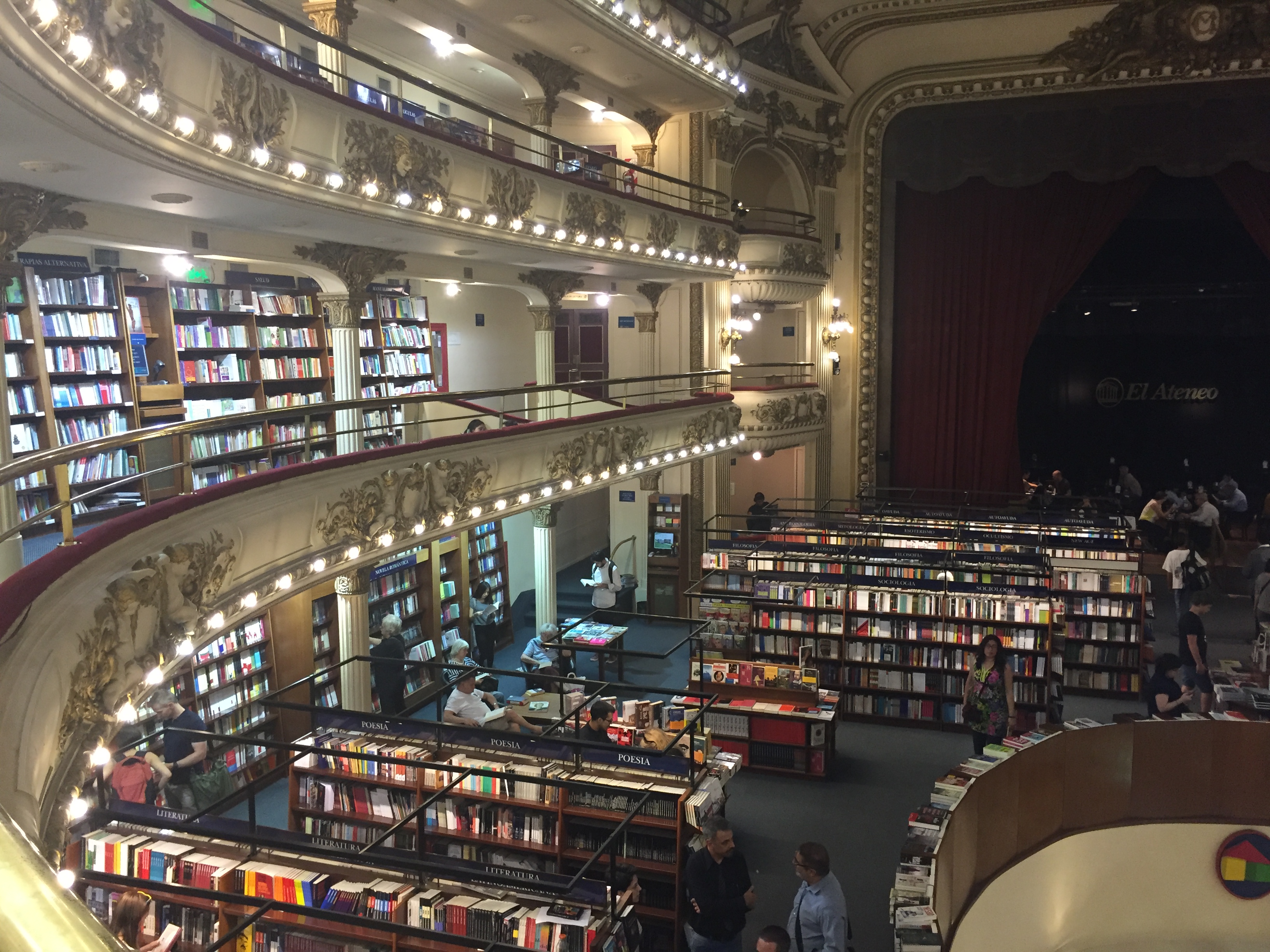

The Argentinian capital is a book lovers’ paradise. Bookstores are everywhere, from the fabulous Ateneo Grand Splendid, housed in a former cinema built in 1919 in the style of the Opéra Garnier in Paris – arguably the nicest bookshop in the world – to the second-hand booksellers in the Mercado Municipal in San Telmo. In the city center, Avenida del Mayo hosts several « confiterías » like Café Tortoni and London City, two old fashioned coffee houses in superb settings where Borges, Federico García Lorca or Julio Cortázar would come to have a drink.

Next to the Café Tortoni is the Museo Mundial del Tango which offers tango classes but which I have not visited. It is however difficult to walk into Buenos Aires without encountering a tango performance, for example on Florida or in the La Boca neighborhood. Many of the couples dancing on the rhythms of the national music are there for the tourists. I am not embarrassed to admit that I fell for it, especially on Plaza Dorrego in San Telmo, sipping a beer while enjoying the dancers’ swinging footwork.

I also watched a few excellent evening tango shows, but what most impressed me is a « milonga » to which I participated in « La Viruta » in the Armenia neighborhood. We arrived around 11 on a Friday night and took a tango class – for beginners of course-. Past midnight, the milonga itself started. With a subtle gesture, men would invite their partners, a woman who often they wouldn’t know. They move to the dance floor and slip, composed and focused on the music and their steps. Class and age differences are ignored for the length of a few tangos.

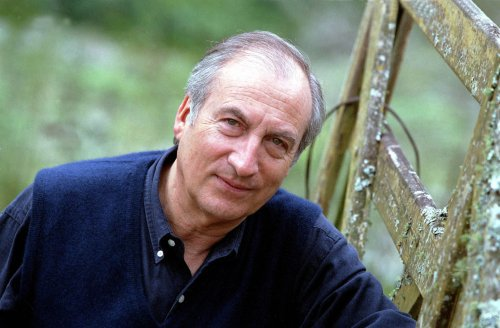

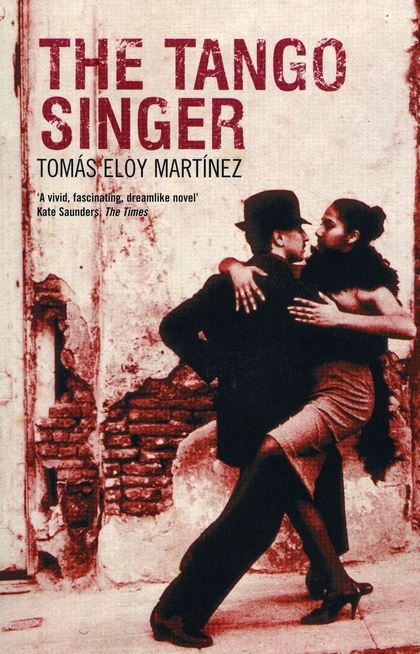

Tomás Eloy Martínez’ novel « The Tango Singer » tells the story of Bruno Cadogan, an American student, who arrives in Buenos Aires in 2001, during the political crisis, looking for Julio Martel a mythic tango singer. This singer who was celebrated in the 40s and 50s as one the most beautiful voices of the genre rarely sings now and his health is deteriorating. He only appears for short concerts, unannounced, in unexpected and surprising spots in the city: next to the slaughterhouse or the « Palacio de la Aguas Corrientes », an amazing palace from the outside but which inside only shelters water tanks and canalizations. Cadogan follows Martel’s trace trying to understand which past secret is hidden behind the labyrinth marked on the capital city’s map by the locations of the singer last performances.

At the same time as it is a tribute to tango, a musical genre born in Buenos Aires’ brothels, Eloy Martínez’s book also brings us back to Borges and his most famous short story « The Aleph », whose title refers to the first letter in the Hebrew alphabet. Next to the pension in which Cadogan is lodging, there is a staircase leading to a basement. From one of the steps, it appears that one can discover the Aleph, this point in the space from which one can see all points, or to use Borges’ words:

“On the back part of the step, toward the right, I saw a small iridescent sphere of almost unbearable brilliance. At first, I thought it was revolving; then I realized that this movement was an illusion created by the dizzying world it bounded. The Aleph’s diameter was probably little more than an inch, but all space was there, actual and undiminished. Each thing (a mirror’s face, let us say) was infinite things, since I distinctly saw it from every angle of the universe. I saw the teeming sea; I saw daybreak and nightfall; I saw the multitudes of America; I saw a silvery cobweb in the center of a black pyramid; I saw a splintered labyrinth (it was London); I saw, close up, unending eyes watching themselves in me as in a mirror; I saw all the mirrors on earth and none of them reflected me; I saw in a backyard of Soler Street the same tiles that thirty years before I’d seen in the entrance of a house in Fray Bentos; I saw bunches of grapes, snow, tobacco, lodes of metal, steam; I saw convex equatorial deserts and each one of their grains of sand; I saw a woman in Inverness whom I shall never forget; I saw her tangled hair, her tall figure, I saw the cancer in her breast; I saw a ring of baked mud in a sidewalk, where before there had been a tree; I saw a summer house in Adrogué and a copy of the first English translation of Pliny — Philemon Holland’s — and all at the same time saw each letter on each page (as a boy, I used to marvel that the letters in a closed book did not get scrambled and lost overnight); I saw a sunset in Querétaro that seemed to reflect the color of a rose in Bengal; I saw my empty bedroom; I saw in a closet in Alkmaar a terrestrial globe between two mirrors that multiplied it endlessly; I saw horses with flowing manes on a shore of the Caspian Sea at dawn; I saw the delicate bone structure of a hand; I saw the survivors of a battle sending out picture postcards; I saw in a showcase in Mirzapur a pack of Spanish playing cards; I saw the slanting shadows of ferns on a greenhouse floor; I saw tigers, pistons, bison, tides, and armies; I saw all the ants on the planet; I saw a Persian astrolabe; I saw in the drawer of a writing table (and the handwriting made me tremble) unbelievable, obscene, detailed letters, which Beatriz had written to Carlos Argentino; I saw a monument I worshipped in the Chacarita cemetery; I saw the rotted dust and bones that had once deliciously been Beatriz Viterbo; I saw the circulation of my own dark blood; I saw the coupling of love and the modification of death; I saw the Aleph from every point and angle, and in the Aleph I saw the earth and in the earth the Aleph and in the Aleph the earth; I saw my own face and my own bowels; I saw your face; and I felt dizzy and wept, for my eyes had seen that secret and conjectured object whose name is common to all men but which no man has looked upon — the unimaginable universe.

I felt infinite wonder, infinite pity.”