I was recently chatting with a Vietnamese friend about books covering her country. We had read some of the same and she also gave me excellent suggestions. Then she asked if I knew about books not talking about the war. A nice love story in Vietnam? She regretted that most novels about her country were either – with a little bit of nostalgia – about the French colonial period, or about the conflicts which tore the country apart from World War II until 1975. She is right. In a previous post, I tried to find books set outside the conflict periods. I have to admit that when they were not about French Indochina, these novels remained strongly influenced by the consequences of war and exile.

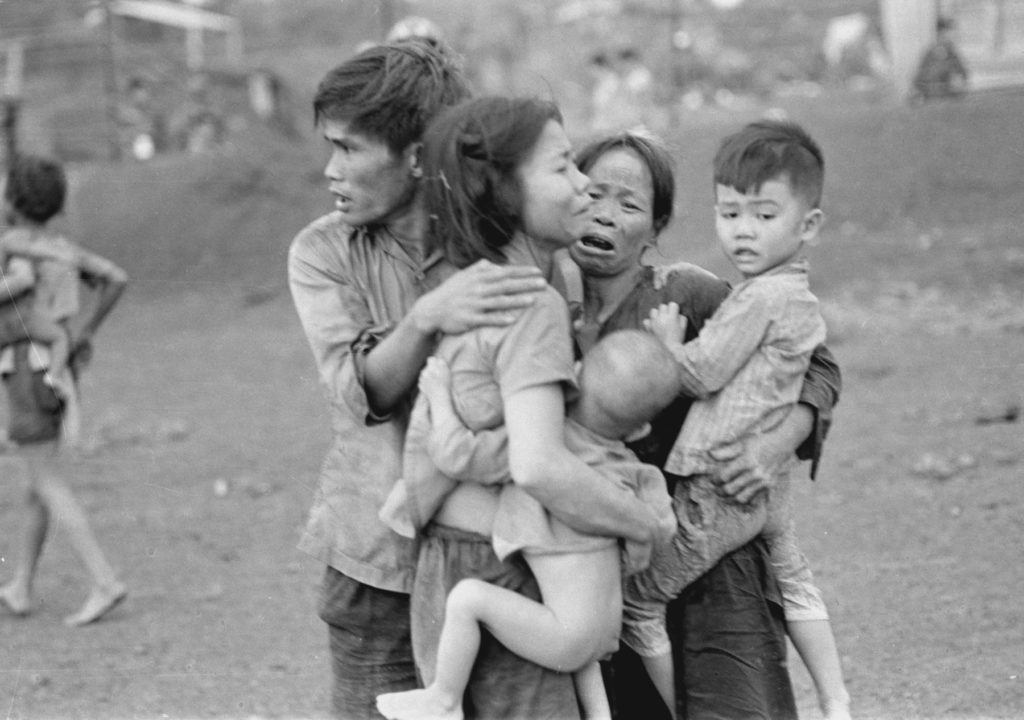

Let’s acknowledge that the decade-long succession of wars in Vietnam has deeply affected the country’ soul. Visiting the War Remnants Museum in Saigon or the Viet Cong tunnels in Cu Chi is sufficient to be convinced. If war played such an indelible role in the literature, let’s address it directly. This is what I am trying to do in this second post about Vietnam. I don’t pretend that by reading these books I have understood everything about the country’s difficult history. But I learned a lot about a conflict that we too often know through Hollywood’s prism: (think of Apocalypse Now, Deer Hunter, Full Metal Jacket, Platoon or Good Morning Vietnam). While doing this, I also read with much pleasure novels that were both very interesting and moving.

As an opening, before the books, I strongly recommend the recent documentary by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick, « The Vietnam War » in 10 episodes and about 18 hours. I watched it this Fall before traveling to Vietnam. The movie, also available in Vietnamese, makes a special effort to present the different points of view: the American ones and the Vietnamese ones. Among the Americans, those who supported and those who opposed the war, among the Vietnamese, the Northern and the Southern perspectives. I learned a lot from this documentary, about the facts and history, but the movie’s power also comes from the numerous testimonies offered by veterans, their families and other key players. Among those witnesses are two writers who wrote about their experiences as soldiers during the war: Tim O’Brien and Bao Ninh.

« The Things They Carried » by Tim O’Brien who was drafted in 1968 at age 22 to serve in Vietnam has become a classic in American literature. My two eldest sons had to read it in high school. I thus took the copy with thorn pages and their penciled notes and I followed the footsteps of those young Americans who left, many of them against their will, to fight in a country of which they knew little without really understanding why. That is the strength of this novel which mixes fiction and personal memories. The reader steps into the narrator’s muddy boots and feels the weight that he and his brothers in arms had to carry: the temptation to cross the border with Canada to dodge the draft, the not so good humor in the platoon, the naïve hope that their girlfriends would remain faithful, the fear of ambushes, the memory of a friend who died stepping on a mine, the remorse after having killed a Viet Cong fighter, the misunderstandings once back home…

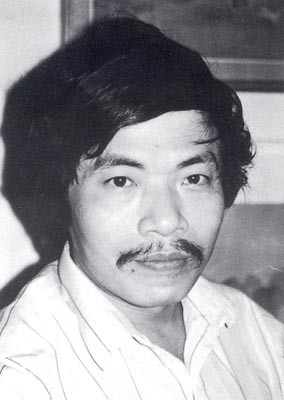

In « The Sorrow of War » Bao Ninh tells the story of ten years of war experienced on the North Vietnamese side. How Kien, a senior in high school enjoying the first emotions of love finds himself in the space of a few days in a train leaving Hanoi for the combat zones in the South. The drama that he and Phuong, his girlfriend, lived through when the train was bombed. And the split that followed and made their love impossible even when they reunited after the war. It is an intense novel and reading it just after Tim O’Brien’s made clear how much, on both sides on the front line, the feelings were similar: fear, easy camaraderie, the obsessive memory of having had to kill for the first time, the sacrifices made by friends or unknown people encountered for few minutes, and despite this, this impression of uselessness and waste that keeps growing over the years after the war.

There is a tendency to focus on what is called in America the Vietnam War and which Vietnamese call the War of Resistance against America or the American War. This is the war that ended the fall of Saigon in April 1975. But let’s not forget that Vietnam was thrown into conflict since the Japanese invasion and occupation after World War II and after in the independence war against the French colonial power (the Indochina War according to the French).

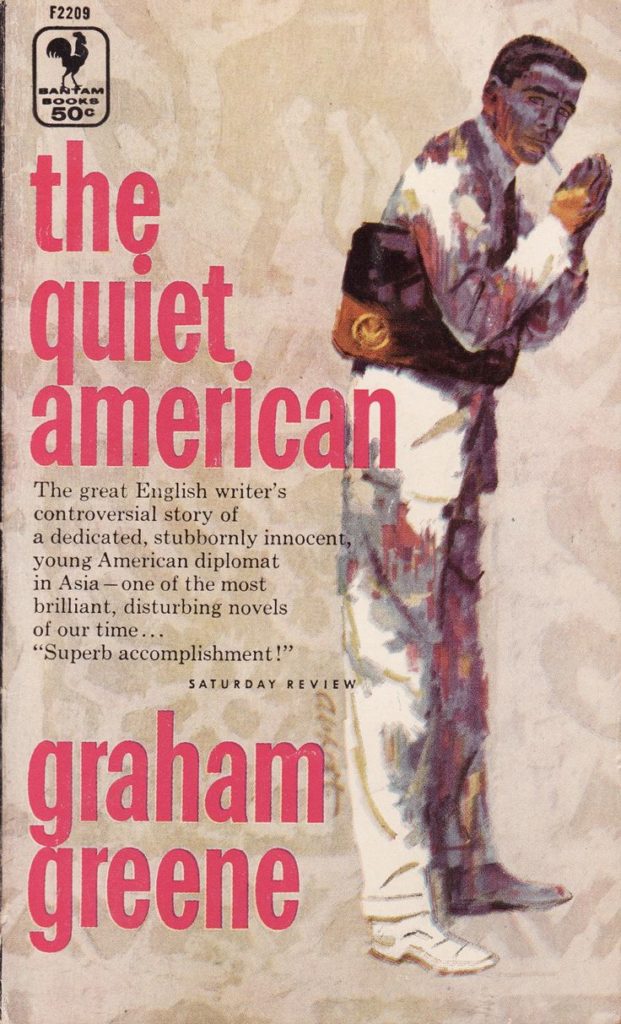

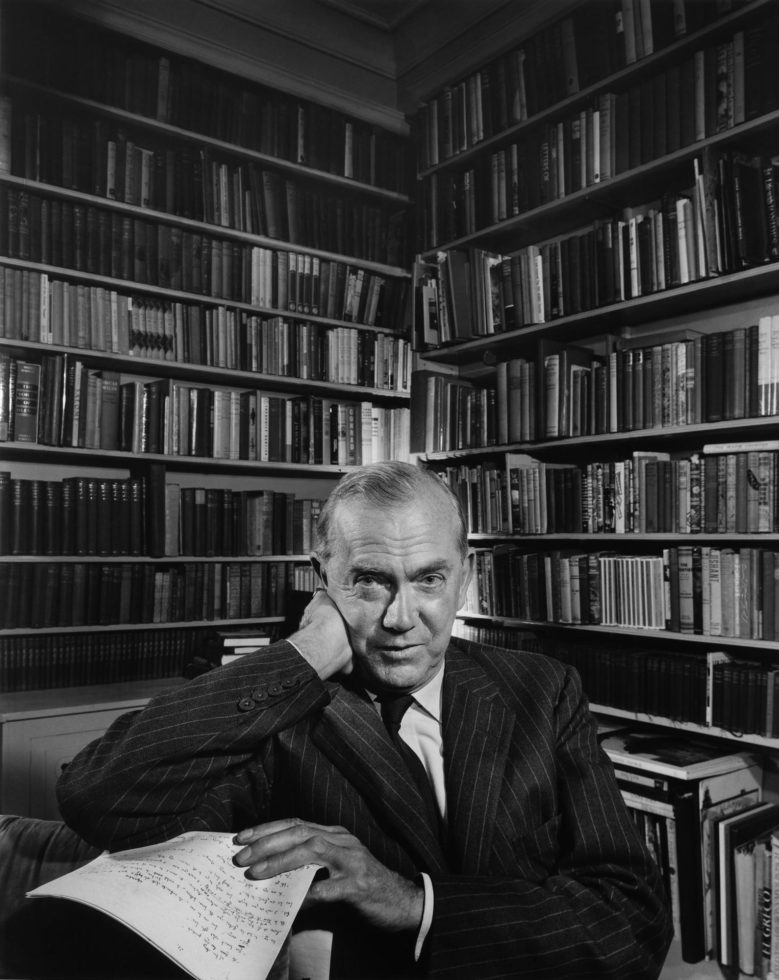

Graham Greene’s novel « The Quiet American » takes place in that era. Written in 1955, it combines two intrigues, one romantic, the other political. Thomas Fowler is an aging British journalist who covers the Indochina War. He gets to know Alden Pyle, a young American freshly arrived in Saigon to lead a medical assistance mission. Pyle falls in love with Phuong, a young Vietnamese woman with whom Fowler is living, and he proposes her. On top of this love triangle played in the legendary hotels and bars of pre-war Saigon, we follow Fowler’s discovery that the mission of this « quiet »American is not that innocent. It is actually a cover for CIA support to groups in the Vietnamese military who are trying to seize power and do not hesitate to let bombs explode in the middle of the city. In addition to his limpid style, the critics have lauded Greene’s perspicacity for having highlighted, as early as in 1955, America’s duplicity in Vietnam. The novel has been adapted in a very good movie with Michael Caine starring as Fowler.

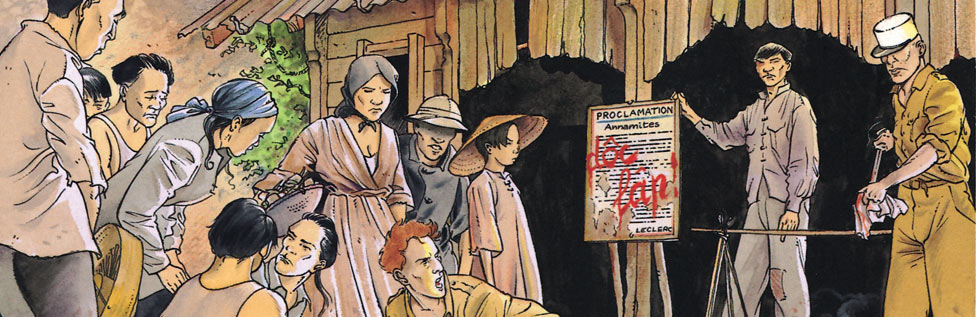

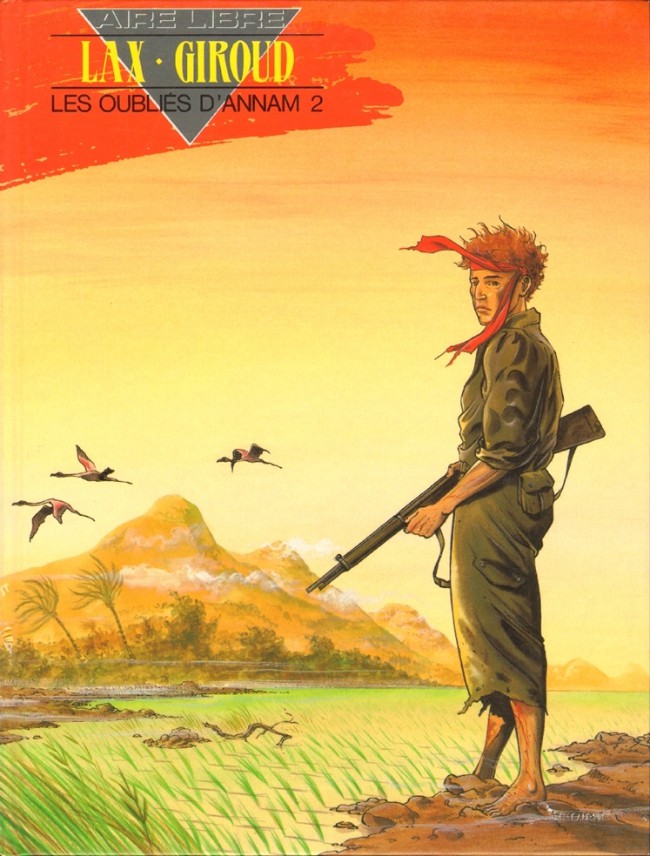

Two sets of graphic novels, not available in English, have also illustrated this period of faltering French power in Vietnam. « Les Oubliés d’Annam (The Forgotten of Annam) » by Christian Lax and Frank Giroud is a two-volume story paying tribute to the French soldiers, some of them still full of enthusiasm after having liberated France from the Nazi yoke, who could not support to serve in an army which placed them on the oppressor’s side. Some took the plunge, deserted and went on the side of the Vietnamese resistance. Traitors or, on the contrary, heroes with a generous heart? In France, most preferred to close their eyes and forget these memories of a dirty war.

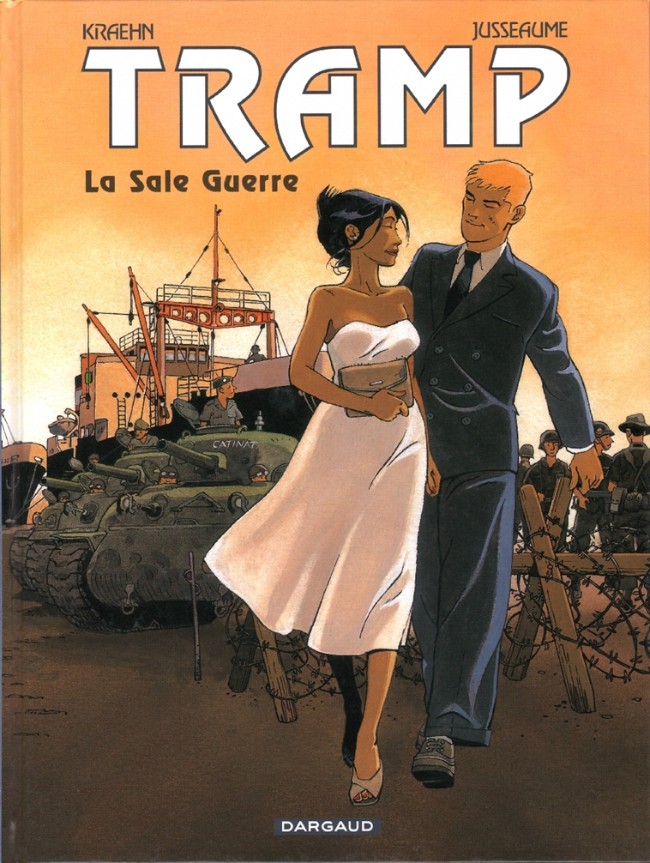

The Asian Cycle (« Escale dans le Passé (Stopover in the Past) », « La Sale Guerre (The Dirty War) » et « Le Trésor du Tonkin (The Tonkin’s treasure) ») in the series « Tramp » by Kraehn and Jusseaume leads Captain Yann Calec from the merchant navy in the muddy atmosphere of a colonial administration losing control and becoming mired in an unwinnable war. At the same time, Calec walks in his father footsteps, a father from whom he kept very hard memories but whom he will get to rediscover.

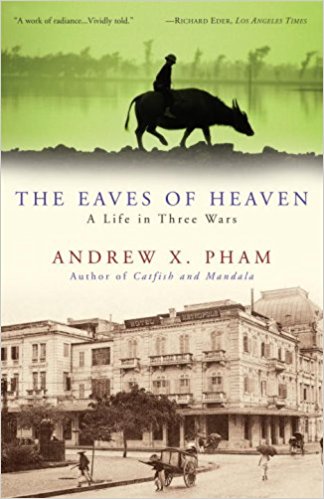

« The Eaves of Heaven » by Andrew Pham is another quest for one’s father. The author, who in « Catfish and Mandala » had described in parallel his exile towards California as a child among the boat people and his journey back to his country of origin as an adult, tells here the itinerary of his father, Thong, during the three conflicts which took place in Vietnam.

Thong was born in a family of landlords in the countryside around Hanoi. His uncle is the local magistrate and his father, the writer’s grandfather, enjoys a French style grand life in the capital. As a young child, Thong discovers the consequences of the Japanese occupation and the rice requisitions imposed by it: hordes of starving people are wandering through the countryside, eating grass and roots and, sometimes the soup that the family estate is able to offer them. After 1945, the young Thong is caught between two fires: he admires the resistance inspired by Ho Chi Minh who recruits inside his village and he abhors the French legionnaires who kill, rape and come to be served from the estate’s granaries, but his family is clearly on the French side and his uncle, the judge, is assassinated by the Communists. The family leaves for Hanoi where the inn they are opening is quickly becoming a convenient place where partying French soldiers bring the girls they have found on the streets. When the French abandon Hanoi, they flee South towards Saigon and start over from scratch as refugees. Thong manages to finish his studies, gets married and a job as a teacher in a small town. But war catches up with him: he cannot avoid being drafted as an officer in the army of South Vietnam and ends up supporting the « strategic hamlets » program devised by the CIA. For a few weeks in 1968, he is demobilized and believes he can go back to a peaceful life, but he needs to go for another tour after the Têt offensive. At the end of the war in 1975, he escapes Saigon with his wife and children, but does not manage to board the last boats leaving. As a former officer from the South, he is interned in a reeducation camp.

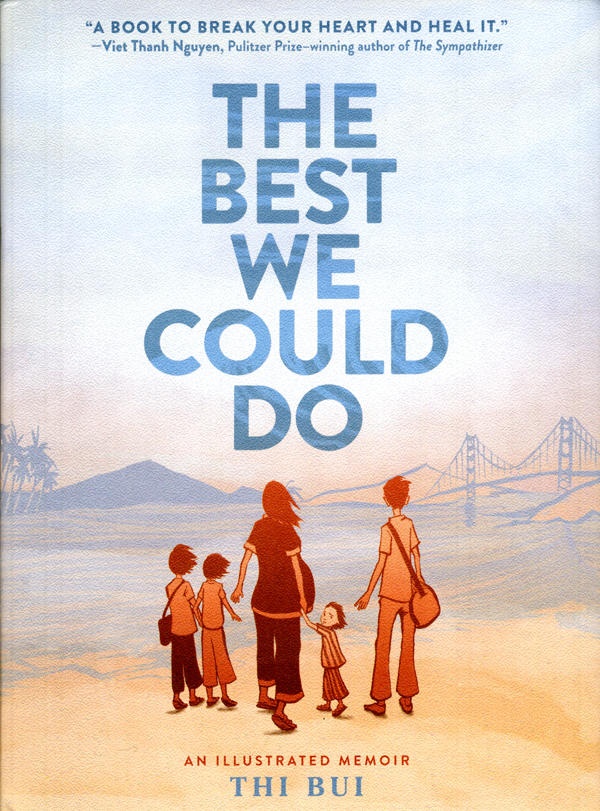

The graphic novel « The Best We Could Do » by Thi Bui, presents itself as illustrated family memoirs. It is a panorama both intimate and powerful that retraces the history of three generations from a Vietnamese family from the war’s onset until their exile in California. Thi Bui starts from the birth of her first child to move up through the history of her father and mother and her grandparents. By doing so, she gets to better understand how their experiences in the conflicts marked them and influenced their roles as parents.

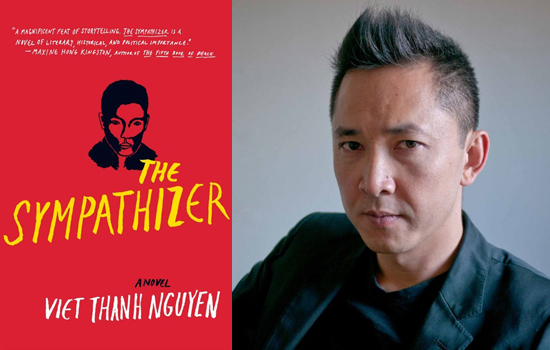

“The Sympathizer” by Viet Thanh Nguyen, a Vietnamese-American academic received the Pulitzer prize in 2016. The novel masterly plays on the double identity theme. The son of a French catholic priest and a young Vietnamese woman, schooled in Vietnam first and later in the US, the narrator is a communist mole infiltrated in the high command of the Southern army. While continuing his work as a spy, he created narrow bonds with high ranking officers and he flees with them after Saigon’s fall in 1975. He ends up in Los Angeles among nostalgic supporters from the Southern regime who are dreaming of staging a coup to get back in power but who meanwhile are managing liquor stores in immigrant neighborhoods. He is hired as a consultant on the set of a Vietnam War movie shot in the Philippines by an Hollywood crew but he does not manage to convince the director to get rid of his caricatural vision of the Vietnamese population. Disobeying the orders from his superior in Hanoi who is asking him to stay in the US, he decides to join in Thailand a group of Southern exiles who are planning a coup. But just after crossing the border, they are quickly captured and he is imprisoned in a reeducation camp and asked to write his confession.