This summer I made a short stopover of just under 24 hours in Moscow. I decided to stay at the Metropol hotel, an Art Nouveau building which is the only hotel in town dating back from before the 1917 Revolution. After the Revolution, it was briefly nationalized under the name « Second House of Soviets ». It was reopened as a hotel in the 1930s and offers close proximity to the Kremlin.

After letting go a strong rainstorm, I left the hotel at sunset to discover the Red Square, cross the Moskva river and walk along it until Gorky Park before returning by metro. I took advantage of the short summer nights to continue my explorations at dawn. All along my perambulations, I was musing « Moscow Nights ». I had just found a wonderful interpretation by Anna Netrebko and Dmitri Hvorostovsky taken during a concert on the Red Square.

It is now a little bit more than 100 years that the October Revolution shook Russia and the world. This event remains not well known and misunderstood, distorted by the prisms of the propagandas that fought each other on both sides of the Cold War and the 20th century’s political chessboards. I read three books to better understand Russia’s history, and Moscow’s during that century.

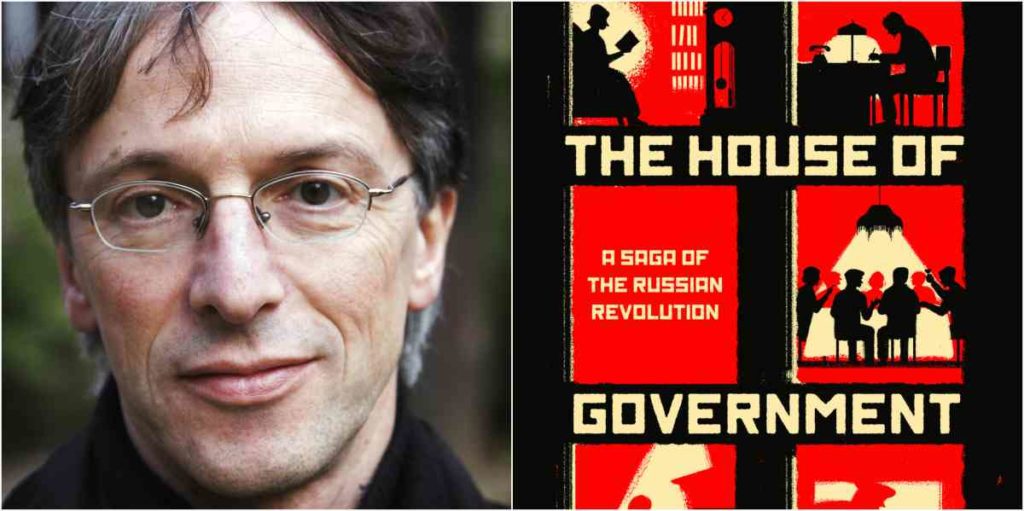

The first of these books is the imposing but fascinating «The House of Government » by Yuri Slezkine, a Berkeley academic born in the Soviet Union. His topic is the huge building which has been called « The House of Government » or « The House on the Embankment» and which was built on the Moskva island to house new nomenklatura’s members and their families. Indeed, with the Revolution, the capital city was transferred from Saint-Petersburg to Moscow and there was not enough space to bring the cadres in a building close to the Kremlin. During the edification of this constructivist giant, the Soviet elite lived in several hotels which had been nationalized, like the Metropol.

Slezkine’s book is half novel, half history essay. Some reviewers described it as the « War and Peace » of the Soviet Union. One difference however with Tolstoy’s saga is that history’s upheavals are not seen through the lens of a few characters. Rather, the reader takes a deep dive in the lives, private and professional, of a multitude of the building’s dwellers about whom Slezkine has collected letters, publications and testimonies which are generously included in the text. Like in several Russian novels, it gets difficult to keep track of all the names, but this is not very important because the author’s purpose is to sketch, through many portraits, the fate of two generations. Those who carried the Revolution with their hands or their heads constitute the first generation. They have experienced prison or exile under the tsarist regime, a period during which was born a very strong camaraderie. Incidentally, they often married among comrades. Within a few months, the Bolshevik leaders seized power and distributed the political, economic and cultural levers to the first hour faithful.

While it gradually appears that the complete advent of the communist dream will not occur immediately, children are born and grow up and a few doubts appear. Marriages between comrades do not always hold up, but who cares, since marriage is a bourgeois and “philistine” institution. The countryside is starving to death but the new elite does not hesitate to claim their access to State dachas, Crimean spa resorts and their caviar quotas.

The Stalinian purges in the late 30s will shake this nice world like a clap of thunder in a calm sky. More than one third of the House of Government’s population will be affected. Today’s accusers and executioners will be among tomorrow’s accused. Nightly knocks on the apartment’s doors have only one meaning: execution for most men, exile for many spouses and fostering among relatives or in a state institution for the children. A second generation which might have lacked the revolutionary fervor of their elders, having been raised in a comfortable cocoon and taught classical literature, but which will soon get the opportunity to prove their valor and their mettle during the Great Patriotic War erupting in 1941 against Nazi Germany.

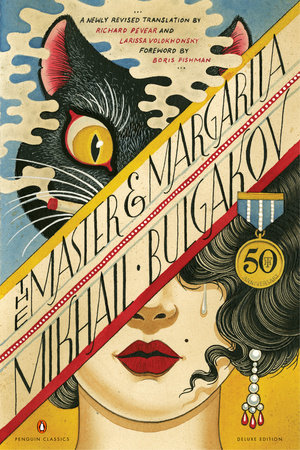

« The Master and Margarita», Russian author Mikhail Bulgakov’s masterpiece takes place during the same period as the golden age of the House of Government. The stylistic contrast between Sletzkine and Bulgakov’s styles is sharp: patient historical reconstruction vs. flamboyant satirical critic. But part of the topic, the deliquescence of a previously revolutionary elite, is the same.

Bulgakov’s novel was written is several steps between 1927 and 1939. Because of censorship, it was only published in the Soviet Union in 1966 with many scenes deleted, but clandestinely published as « samizdat (self-edition) ». It is a fascinating book, at the same time burlesque and deep, juxtaposing three stories that ends up merging into one. Satan, under the guise of Woland the magician, arrives in Moscow to sow trouble among the world of the official writers of the Soviet Union, a nomenklatura of profiteers consumed by petty squabbling and bickering.

The Master is an embittered writer whose novel about the encounter between Pontius Pilate and Jesus has been rejected by the ruling clique of littérateurs. He retires from the world, leaves his beloved Margarita and checks himself in a psychiatric institution. The story of the fascination that Pontius Pilate starts to develop for the one who he will nevertheless condemn takes place in Jerusalem and is Bulgakov’s novel second axis. Margarita’s character is the focus of the third story. She makes a deal with Satan: she obtains supernatural power allowing her to fly over Moscow and Russia and take revenge on her husband’s persecutors in exchange for agreeing to play the role of hostess during a ball that he gives in Moscow on Holy Friday’s night.

In a previous article, I covered the second World War period in the Soviet Union with the book “The Unwomanly Face of War » by Svetlana Alexievich, who like Sletzkine recomposed a period, its daily life, emotions and consequences, by collecting and organizing a large body of individual testimonies.

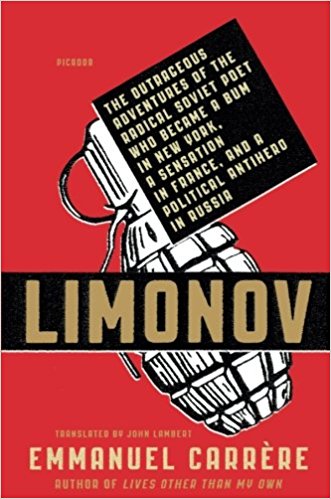

With « Limonov », by French novelist Emmanuel Carrère, we get a completely different approach to look into the second part of the Soviet history. This superb fictionalized biography – which earned the Prix Renaudot in France in 2011 – tells the story of Edouard Limonov, born in 1943. By following this atypical individual, writer and poet, dissident and adventurer, Carrère helps us discover the reversal of fortunes and sometimes the contradictions of life in Russia before and after the fall of Communism. Limonov, whose father is a bland NKVD agent who guards prisoner trains heading for the gulags, lives a dull childhood and a rebellious adolescence in a grey suburb of Kharkov. He goes to Moscow where he joins an underworld of dissident artists and writers at the time of Brezhnev’s “soft Stalinism”. He manages to emigrate to New-York, ends up almost homeless before being hired as a butler by a billionaire. He writes a few autobiographical pieces with provocative titles (« The Russian Poet Prefers Big Blacks », « Journal of a Looser ») which are noticed in France. In 1980, he moves to Paris, becomes a sensation among a certain intelligentsia and meets for the first time the young Emmanuel Carrère.

After the fall of the Berlin Wall, he goes back to Russia and visits his family in Kharkov. He somehow ends up embroiled in the former Yugoslavia wars, on the side of the Serbian nationalists. He is seen next to Radovan Karadzic as Sarajevo is bombarded. The former dissident who was a media’s darling is now a pariah in the Western world. In parallel, he gets involved in Russian politics. He is one of the founders of the « National-Bolshevik » party – Limonov never shies away from provocation – is several times arrested and jailed and becomes one of the most visible opponents to Vladimir Putin.

A complex, surprising, fascinating, sometimes shocking itinerary, a little bit an image of post-communist Russia which many Westerners struggle to understand.