The Red Army. For me, born at the end of the 60s, this is a name evoking the Cold War and the televised images of parades in front of the Kremlin on May 1st or at the funerals of the Soviet gerontocrats: Brezhnev, Andropov, Chernenko…Or rather the full and deep voices of its choirs. If I dig into my history classes, I remember that the same Red Army fought on the side of the Allied against Nazi Germany and that their obstinate and heroic resistance in Stalingrad marked the beginning of the end for the 3rd Reich.

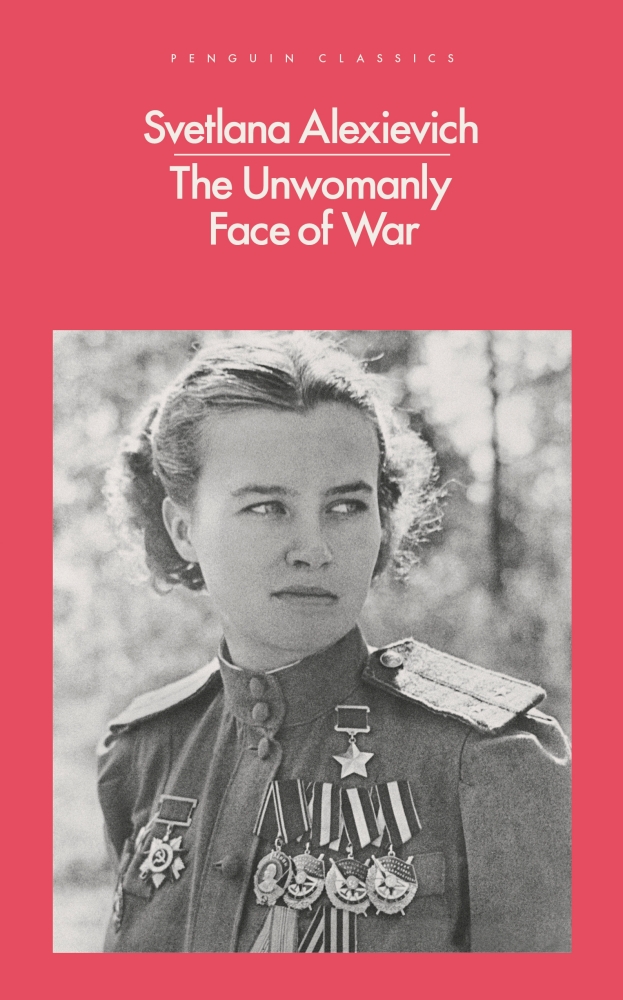

It’s equipped with these few priors that I started reading “The Unwomanly Face of War » by the Byelorussian writer Svetlana Alexievich. The book collects and organizes testimonies by women who have served in the Red Army during World War II, from 1941 to 1945. In assembling these testimonies, the writer puts herself between journalism and fiction. It is a style that she used in subsequent works on the nuclear catastrophe in Chernobyl (Voices from Chernobyl) or the Afghan War (The Zinky Boys). This style was hailed by the Nobel Committee when she received the 2015 Literature Prize.

In using stories told by ordinary witnesses, far from chancelleries and military headquarters, she also wants to describe history as it has been lived day-by-day, with its enthusiasms, its sufferings and anxieties. The “Great Russian Patriotic War » takes very different colors when told by women, often very young, who volunteered to join in their motherland’s defense.

For example, Nina Yakovlevna Vichnevskaya, Sergeant Major, medical assistant of tank battalion said:

“Where shall I begin? I’ve even prepared a text for you. Well, all right, I’ll speak from the heart…This is how it was…I’ll tell you as I would a friend…

I’ll begin by saying that girls were accepted reluctantly into the tank forces. One could even say they weren’t accepted at all. How did I get there? We lived in the town of Konakovo, in the Kalinin region. I had just passed my exams to go from junior high to high school. None of us understood then what war was; for us it was some sort of game, something from a book. We had been brought up on the romanticism of the revolution, on ideals. We believed the newspapers: the war would soon end in our victory. At any moment…

Our family lived in a big communal apartment. There were many families in it, and every day somebody left for the war: Uncle Petya, Uncle Vasya. We saw them off, and we, the children, were mostly overcome by curiosity. We went all the way to the train with them…Music played, women wept, but none of that frightened us; on the contrary, it amused us. The brass band always played “The Slav Girl’s Farewell”. We, too, wanted to get on the train and leave. To that music. The war as we pictured it was somewhere far away. I, for instance, liked uniform buttons, the way they shone.”

Stories follow each other. Some are funny, like when the girls need to make do with uniforms designed for men. Others are very moving when they remember young men dying in their arms or soldiers – Soviets or Germans- agonizing along the roads on which they were marching.

After having finished « The Unwomanly Face of War », I took advantage of three trips in the former Soviet Union, in Armenia, in Tajikistan as well as a short stopover in Moscow, to go looking for monuments commemorating the 1945 victory and the sacrifice of those who died for the motherland. Photographs from monuments in Garni close to Yerevan, in Dushanbe and at the Kremlin illustrate this article.

Those monuments are full of patriotic fervor and stoical fighting spirit. They are therefore quite different than the lively and moving testimonies assembled by Alexievich. They mainly represent men. Maybe the latter explains the former. Decidedly, the face of war is unwomanly.

Is it for that reason that women in the Red Army did their best to quickly forget the war, as explained by Valentina Pavlovna Chudaeva, Sergeant, Commander of anti-aircraft artillery:

« We left for the front at the age of eighteen or twenty and came back at twenty or twenty-four. First there was joy, but then fear: what were we going to do in civilian life? There was a fear of peaceful life…My girlfriends had managed to finish various institutes, but what about us? Unfit for anything, without any professions. All we knew was war, all we could do was war. I wanted to get rid of the war as quickly as possible. I hastily remade my uniform coat into a regular coat; I changed the buttons. Sold the tarpaulin boots at a market and bought a pair of shoes. When I put on a dress for the first time, I flooded myself with tears. I didn’t recognize myself in the mirror. We had spent four years in trousers».

The men coming back from the front were heroes. The girls, for their part, needed to erase their years at the war if the wanted to be coveted women and respected spouses. That’s why gradually their role became forgotten. Svetlana Alexievich’s patient work was necessary to rediscover and reestablish this hidden face of history.

***

A few days after his untimely death, I cannot resist to the pleasure to end this article with two World War II Russian songs interpreted by the Siberian baritone Dmitri Hvorostovsky, accompanied by the Red Army Choirs. The first, « Katyusha », sung for the first time in 1941 by female students bidding farewell to soldiers departing to the front. Still, it is an example of the traditional vision of women’s role during the conflict. Katyusha remains in the village and faithfully for her beloved to come back:

« Let him preserve the Motherland

Same as Katyusha preserves their love»

The second one, « Zhuravli » or « Cranes » evokes the souls of those who never came back:

“I sometimes think that the fallen soldiers

Who have not returned from fields of blood

Never lied down to rot beneath our soil

But must have flown off as white cranes…”