The Dutch are known for their frankness and their taste for transparency which would trace their origin in Calvinism. Calvinism arrived in the Netherlands in 16th century and established itself as the dominant religion during the 17th century, the Dutch Golden Age. It is said that traditionally, Dutch houses had no curtains because good citizens had nothing to hide from their neighbors. Evolving over the course of generations from transparency to tolerance, is this the source of the red-light windows attracting scores of tourists going out at night in Amsterdam?

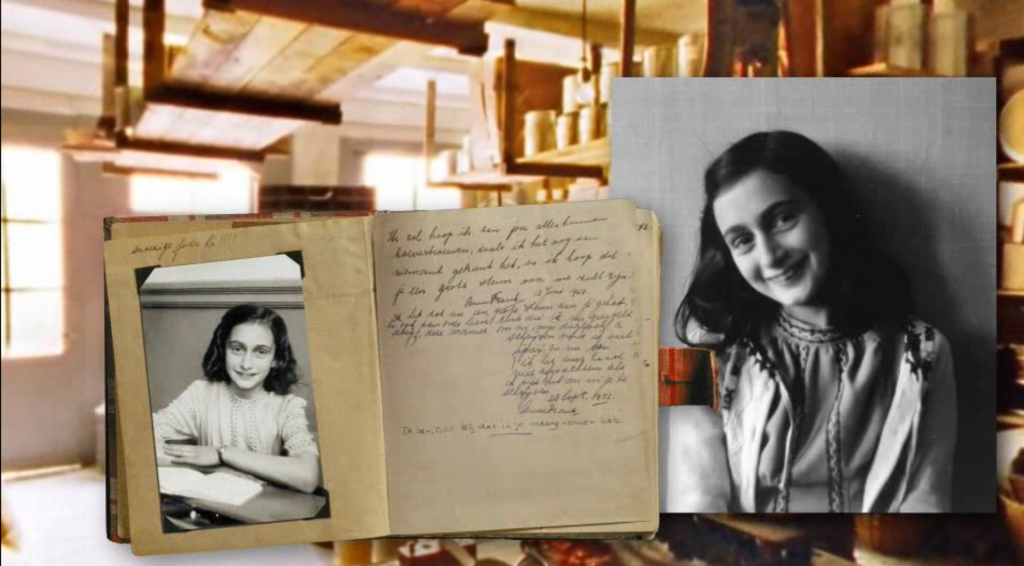

However, a careful walk along the canals could reveal many secrets. A few yards from the Oude Kerk, the oldest church in the city which went from Catholic to Calvinist during the Reformation and which is now located in the middle of the prostitution district, it is possible to visit « Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder (Our Lord in the Attic) », a Catholic church hidden on the third floor of a merchant house. From the canal, nothing betrays this clandestine church where mass was said when, in the Netherlands, the Catholic religion was forbidden – and later tolerated only on the condition of avoiding any public display. Similarly, in the charming béguinage (Begijnhof), the beguines had been allowed to stay but had to follow the Catholic services in a chapel hidden in a house. And of course, Amsterdam is also where Anne Frank wrote her journal in the « annex », the secret extension of a company house, which was concealed behind a retractable book case, before being arrested with her family and deported to the Nazi extermination camps.

Ons’ Lieve Heer op Solder (Our Lord in the Attic) Photo: ©Travel Addicts – 2016. Used with permission https://traveladdicts.net/our-lord-in-the-attic-amsterdam/

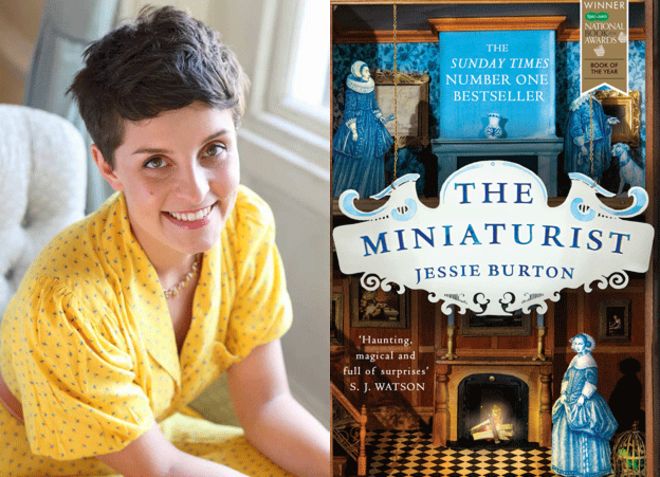

This tension between transparency and secrets, between Rembrandt’s flamboyant “Night Watch” and Vermeer’s intimate compositions, between the puritan frugality of the portraits of merchants dressed in black with simple white lace collars and the exuberant ostentation of some still lives, can also be found in the Rijksmuseum. This a wonderful museum celebrating the Dutch Golden Age, the period when the proud Republic was establishing commercial outposts in every corner of the globe and competed in wealth and power with England. It is in one of this museum’s rooms that we can admire Petronella Oortman’s dolls’ house. This exceptional replica of the house in which Petronella Oortman lived with her husband Johannes Brandt, a rich merchant, served as starting point and inspiration for the « The Miniaturist » the captivating novel by Jessie Burton, a young British novelist.

Burton imagines the life of Petronella – Nella- a young penniless aristocrat who came from the countryside to get married with the wealthy Johannes, and live in a patrician house on the Herengracht in Amsterdam. Johannes travels and trades around the world, but ignores his spousal duties. Is he looking for forgiveness when he offers his wife a doll’s house, a perfect copy of their own dwelling? The young spouse is upset at first: is she considered as a young girl that one hopes to console with a toy, albeit a sumptuous one? Gradually she needs to find her place in that house, which in Johannes’ absence, is led with austerity by his sister Marin, supported by two servants: Cornelia, an orphan, and Otto, a former slave from Dahomey.

Nella requests the services of a miniaturist to complete the decoration and the characters in her house. The pieces which are delivered are perfect and their realism is astonishing. But soon these objects arrive without having been ordered and seem to anticipate the events and dramas that will affect the house. Who is making these miniatures? Is this the blond woman who seem to follow Nella with her piercing blue eyes when she ventures along the canals? What does she want? Warn? Punish? As secrets are let in the open, as ruin and scandals threatens, Nella is left on her own to take the reins of her house and face the opprobrium of the self-righteous.