In 1993, I made a wonderful trip about one month and half long in China. We entered the country from the West on the Karakorum Highway which, climbing above 5000 meter, brought us from Pakistan to Kashgar. From Xinjiang, we progressed through very long train or bus journeys of varying comfort levels: Urumqi, Dunhuang, Lanzhou, Xian and finally Beijing. Before zipping South via Shanghai to Guangxi and Yunnan. For a young European student, it was difficult to imagine a more radical change of scenery. We traveled through a series of fabulous landscapes: a Tibetan monastery on the slopes of green rolling hills, the deserts around Turfan’s oasis, bike wanderings in the rice fields around Guilin. We visited Kashgar’s animal market and admired the horse showmen. We had a surprise encounter with a street opera in Lanzhou during which actresses with tons of make-up were playing for laughing bystanders and amazed children. In Lijiang’s steep streets, we walked along old Naxi ladies, somewhat wrinkled under their heavy burden, and we wondered whether living in a matriarchal society had made their lives any easier.

We got caught in the mass of bikes stopping for red lights in Beijing. The side lanes reserved for bikes were very crammed, while only a few taxis or buses would use the much larger center lanes on the avenues. I recently went back in Beijing: cars traffic jams are now common place and I am not sure I would risk riding a bike. But it was still possible to find the atmosphere of the hutong, the city’s traditional neighborhoods by lodging in one of their courtyard hotels.

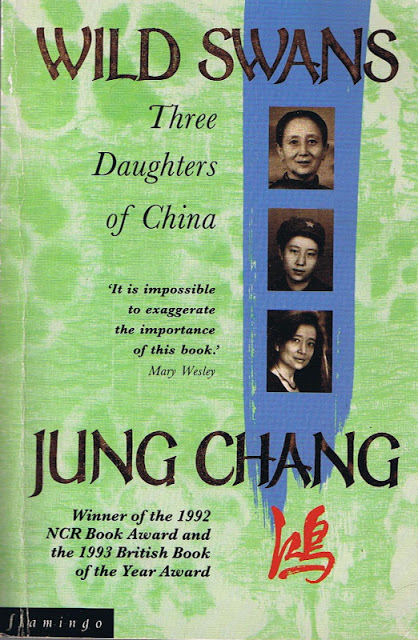

« Wild Swans. Three Daughters of China » by Jung Chang was published in 1991, two years after the Tiananmen square events. I just finished reading this immensely successful book. I would have loved to read it during my 1993 Chinese journey, but I don’t know how I would have done to hide it in my luggage at customs or to read it while on the train: the book was censored. Nowadays it remains officially prohibited in China, even though it is circulated.

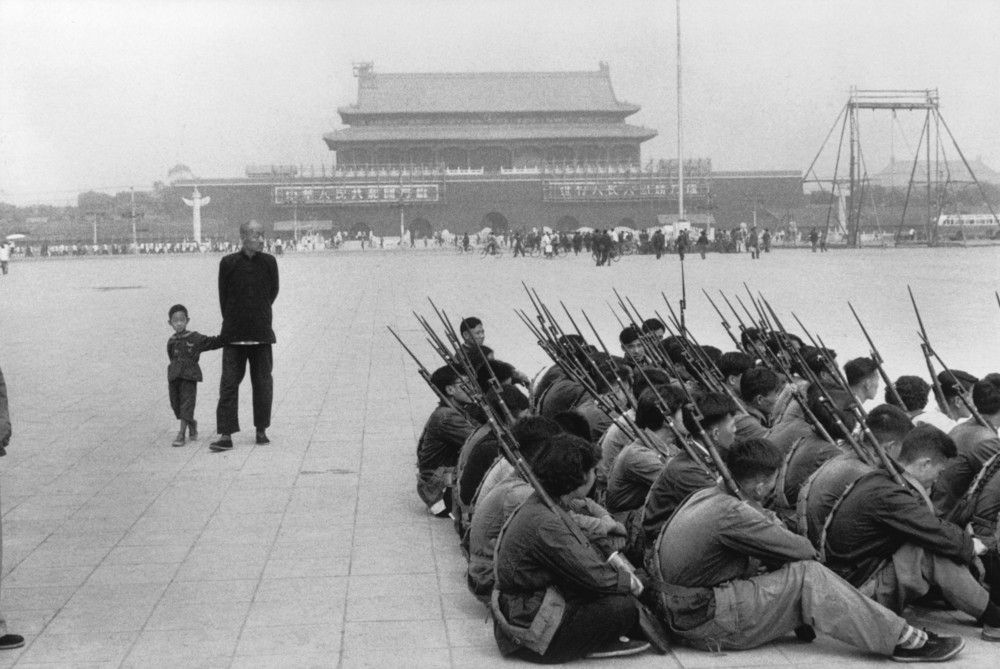

« Wild Swans » tells the true story of three generations of Chinese women over close to a century: Yu-Fang, born in 1909 under the « ancien régime » and whose feet were bound to make her more attractive became a warlord’s concubine in Manchuria, before marrying a doctor. Her daughter, Bao Qin, born in 1931 grew up under the Japanese occupation and at 15 became a communist militant after seeing the abject poverty in which people were living. She married a young cadre from the Party in Sichuan and moved there. Revolutionary enthusiasm was followed by the relative comfort of a family of respected and incorruptible apparatchiks before making place to disillusions and persecutions during the Cultural Revolution. Jung Chang, the author, is their grand-daughter and daughter. She is a teenager at the time of the Cultural Revolution: she joins the Red Guards, goes to Beijing in crowded trains to be part of the marches proclaiming support for Chairman Mao. She is also sent for reeducation to work among the peasants in the mountains of Sichuan. Like her parents, she gradually becomes wary of the cult of personality surrounding the Great Helmsman. In an era dominated by suspicion and denunciations, she nevertheless manages to get a hard-sought spot at the university where she learns English. She obtains a fellowship to study in London where she currently lives.

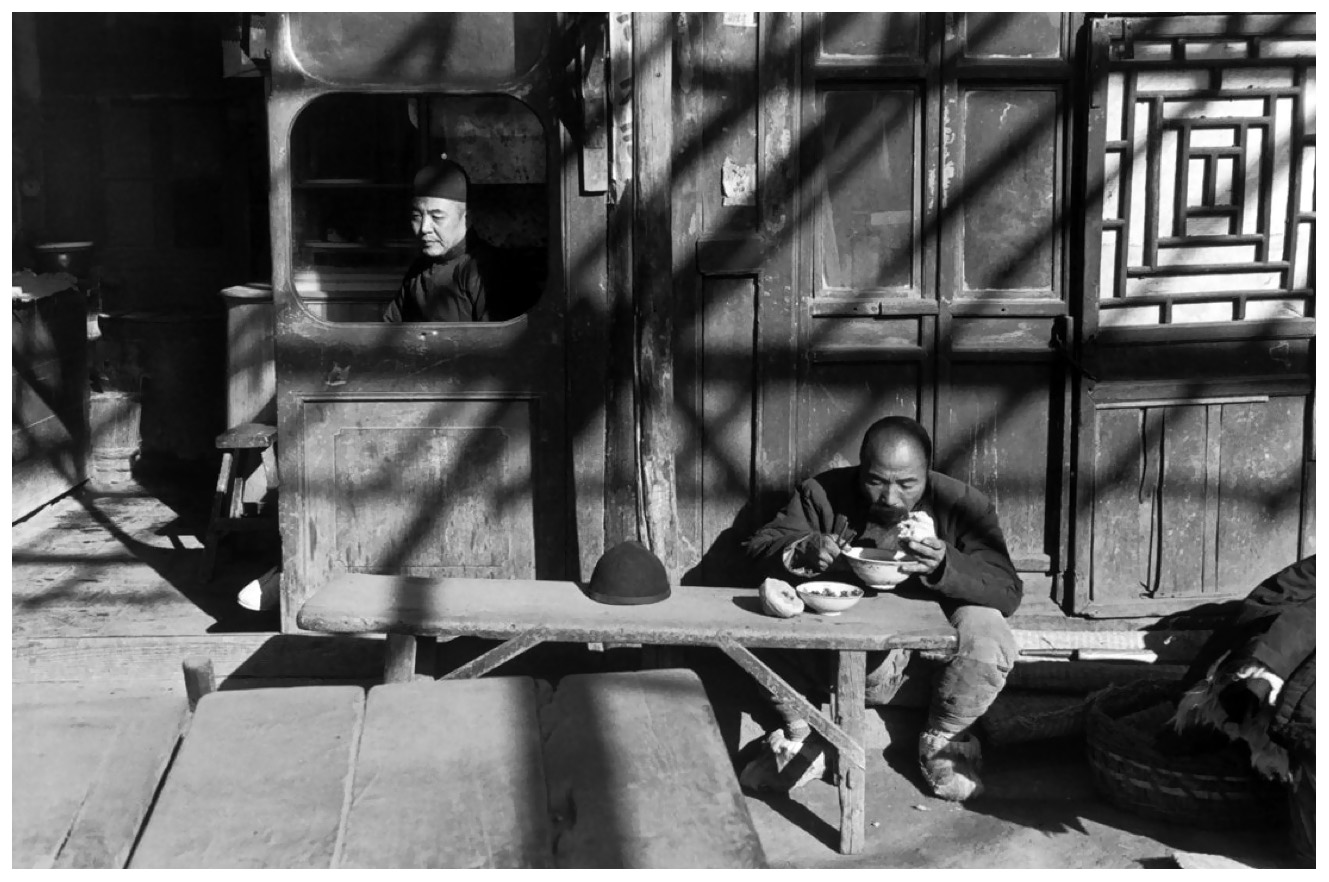

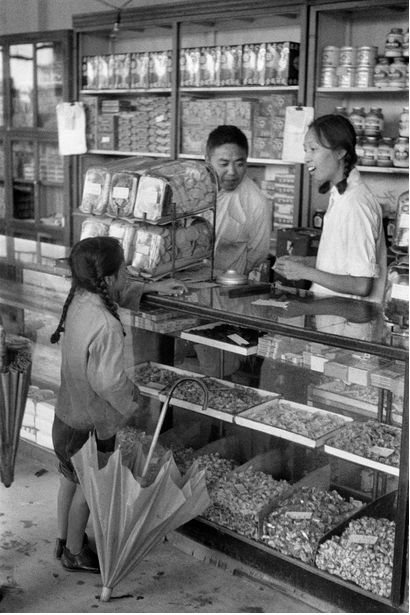

This is a fascinating story which mixes the history – often violent- of a country still poorly understood in the West (hard to understand how an entire Western intelligentsia could have claimed to be Maoist!) with the emotions and aspirations of family members, with their daily concerns, marriage dynamics and complex relationships across generations. For those who seek an in-depth understanding of China and its recent history, I strongly recommend reading it. This is also an example that personal stories, when they are written with talent and with the necessary distance, are, at least for me, a richer way to approach history than the work of professional historians. To illustrate this post, I have selected a few photographs from Henri-Cartier Bresson. The French photographer witnessed, with great attention for the men and women engulfed by them, the great historical upheavals which shook China and mark the pulse in Jung Chang’s book.