One of my first trips to Ghent had a very precise objective: I had asked my mother to take me to the St Bavo’s Cathedral to discover the Ghent Altarpiece (The Adoration of the Mystic Lamb) by the van Eyck brothers. I was 14 or 15 and I had picked this Early Flemish masterpiece as the subject of a school presentation. The altarpiece was still exhibited in one of the Cathedral’s side chapel and not yet in the previous baptistery whose security has been reinforced to protect against theft. I kept a wonderful memory from this visit. It was probably one of the first times that I was so curious and focused on an art piece’s history and details.

« War and Turpentine (Oorlog en terpentijn) » by Stefan Hertmans delightfully reminded me of the association between fine painting and Ghent, this superb Flemish city at the confluence of the Leie and Scheldt rivers. The book – which I unfortunately did not read in the original Dutch – was directly inspired by notebooks left to the author by his grandfather. He waited thirty years to open them, but the result is a beautiful tryptich: a youth experienced in poverty before 1914 in a world which has now disappeared, the war and the inanity of its acts of heroism, and finally the long following years, lived in the halftone of an unaccomplished love.

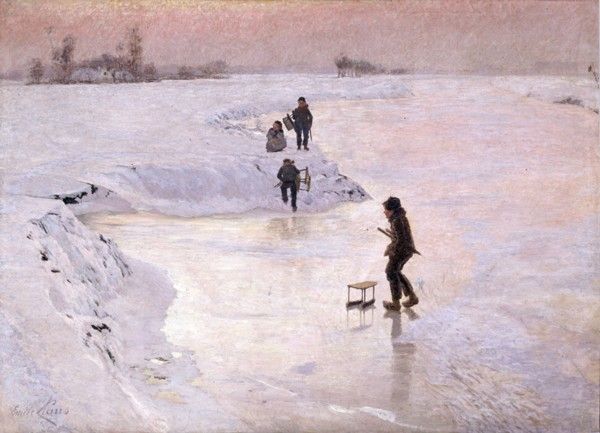

The author’s great-grandfather, and the main character’s father, was a church painter, working on frescoes in many of the religious buildings scattered across the city. He was a focused and enthusiast artisan who died early, probably for having been exposed too much to the lead contained in his colors. We are at the beginning on the 20th century in a modest, pious and conscientious environment. The son, Urbain Martien, likes to go with his father to the cloisters and dining halls of the convents to see him paint on the scaffoldings. But the good fathers don’t pay well their artists and Urbain needs to leave school early to find a job. He almost loses one foot in a foundry, and does some odd jobs, including one for a tailor established on the Kouter, a large square, next to the Hôtel Falligan, a very nice rococo house which hosted and still hosts the « Société Royale Littéraire de Gand ».

The author’s great-grandfather, and the main character’s father, was a church painter, working on frescoes in many of the religious buildings scattered across the city. He was a focused and enthusiast artisan who died early, probably for having been exposed too much to the lead contained in his colors. We are at the beginning on the 20th century in a modest, pious and conscientious environment. The son, Urbain Martien, likes to go with his father to the cloisters and dining halls of the convents to see him paint on the scaffoldings. But the good fathers don’t pay well their artists and Urbain needs to leave school early to find a job. He almost loses one foot in a foundry, and does some odd jobs, including one for a tailor established on the Kouter, a large square, next to the Hôtel Falligan, a very nice rococo house which hosted and still hosts the « Société Royale Littéraire de Gand ».

I have been invited to some parties in this club, the gathering place for Ghent’s Francophone high society, which is known in the book and in the city in general as the « Club des Nobles ». A quiet reminder that in Flanders, the vicissitudes of Belgium’s history, switching quickly from Napoleon’s Empire to the Kingdom of the Netherlands before proclaiming its independence – at first in French only – in 1830, led to this strange situation which remains at the heart of the Belgian linguistic dispute: for too many years, the ruling classes spoke French while the people spoke Flemish.

After those different jobs, Urbain registers at the military school. This training will allow him to play a leadership role among the other conscripts when the First World War starts and Germany invades Belgium despite its neutrality. The Belgian army is ill-prepared, and in spite of some heroic actions, it must withdraw behind the Yser river, for long years of war in the trenches. Urbain Martien behaves as a hero and often volunteers with his group. Injured and decorated several times, he is sent back to the frontlines after each convalescence in the English hospitals. Slowly but surely, however, the mud, the cold, the insalubrity, the pointless attacks, useless deaths and the haughtiness – expressed in French – by some of the officers will end up undermining the enthusiasm of this exemplary soldier.

Back from the trenches, he gets back to Ghent, his family and his mother. He also falls in love with the beautiful Maria-Emelia. The families are getting to know each other, but the Spanish Influenza takes away the fiancée before the wedding. Finally, he ends-up marrying the elder sister, Gabrielle, but this is a conventional, loveless union. The war memories and traumas and this aborted love will transform Stefan Hertmans’ grandfather into a taciturn man who seeks refuge in painting and specializes in copying the masterpieces: Rembrandt’s Man with the Golden Helmet or Vélasquez’ Venus at her Mirror (aka Rokeby Venus). It is only many years later that the grandson will realize that the face in the mirror is not an exact copy of Vélasquez’ painting, but a representation of the woman he loved and who disappeared too early.