I have a special attraction for seaplanes. Is this a remembrance from my readings of the Tintin comics? Or because I have only seen a few (I remember one landing on a Norwegian fjord)? Or is it the feeling of freedom suggested by this aircraft which, provided there is enough water around, seems able to take off and land pretty much anywhere.

During my visit to Vancouver – it was a rainy November week – seaplanes were everywhere. I discovered them coming and going when arriving at the conference center as the sun was rising through the clouds on the harbor and I remembered the first line of Marcel Thiry’s poem « You Who Pale at the Name of Vancouver (Toi qui pâlis au nom de Vancouver) ». A seaplane was parking along the dock just below the Convention Center’s terrace. Another one left a few minutes later. Despite the ever menacing rain, I walked a lot during my stay, in particular towards Stanley Park and its views on the sea, the city and the mountains. Many times I lifted my head to follow a seaplane taking off or landing, like an invitation to the islands of the Pacific North West.

One morning, the clearing clouds let the first snow appear on the mountains’ tops. Vancouver is this fascinating city in which in winter, while the snow is absent from the city center, one municipal bus ride across Lions Gate Bridge and one lift in a cable car are enough to reach in one hour the ski slopes and the fresh powder.

Doctor Asher is one of the characters in Alice Munro’s short story “What is Remembered” published the collection “Hateship, friendship, courtship, loveship, marriage”. He is a bush doctor who is moving around with his aircraft. It is not said whether it is a seaplane. It is by plane that he came from one of the British Columbia islands to Vancouver for Jonas’ funeral, who was one of his patients.

Jonas was also one of Pierre’s childhood friend. Pierre also came to the city for the funeral, together with Meriel, his wife. She would like to take advantage of her visit in the city to pay a visit to Aunt Muriel, one of her mother’s friend, whose first name she inherited before it was modified. Pierre needs to hurry up to catch the ferry to get back to their children and release the babysitter. The doctor offers to drive Meriel in his rental car to the residence for seniors where Aunt Muriel is living. The Aunt suffers from cataracts and asks upon their arrival:

“What’s your husband’s name?”

“Pierre.”

“And you have two children, don’t you? Jane and David?”

“That’s right. But the man who’s with me –”

“Ah, no,” the old Muriel said. “That’s not your husband.”

Later, alone on the ferry’s deck under a drizzle, Meriel remembers the rest of the day: the drive to Stanley Park, their kiss in public at Prospect Point where she told him « Take me somewhere else », the flat near Kitsilano Beach where he was staying and where he takes her…

Much later, after the doctor’s death in a plane crash – she saw his picture in the paper – and after her husband’s death, she would also remember that the doctor refused her a goodbye kiss when he dropped her at the ferry’s jetty (« No. I never do. »).

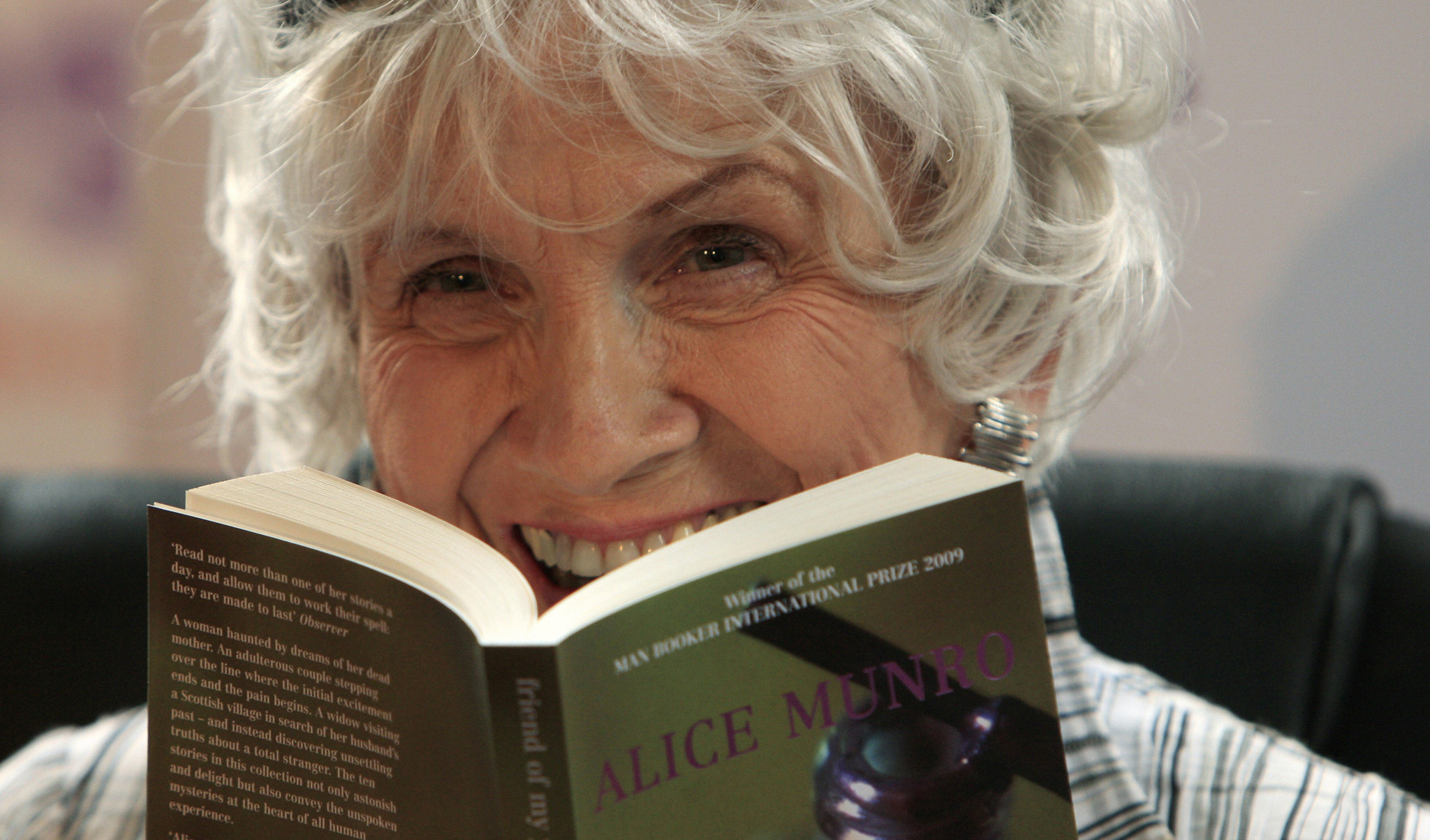

That story is a superb example of the art of the short story as practiced by Alice Munro. When she received the Nobel for literature in 2013, the Canadian octogenarian was compared to Chekhov and celebrated at the “Queen of the short story”. Many, including me, discovered then those perfectly cut diamonds. Most of her stories take place in the provincial cities of her native Ontario, but in the 50s she lived for a few years in Vancouver with her first husband. It was a time of her life when, as she writes in « What is remembered », the husbands were starting serious and resolute lives (job, mortgage) while their wives could allow themselves to fall back into some sort of second adolescence.