It was sunset, and a few pirogues were crossing the river. I was sitting on the terrace of a restaurant along the Ubangi river, sipping a beer with a colleague. We were in Bangui on the Centrafrican side, facing the territory of the Democratic Republic of Congo on the opposite bank. My first vision of the Congo. If you look at the covers of the books I discuss in this post, this image of a river on which progresses a pirogue pushed by a standing man seems to be one of the symbols of life in Congo.

The idea to go on board one of these pirogues was tempting, but we didn’t do it since we had no visa. A few months later I had planned to visit the Virunga National Park in Eastern Congo, but the political turmoil in the Kivu Province made it impossible. I couldn’t go further than the border post between Gisenyi in Rwanda and Goma in Congo. I had the feeling that I was going around this gigantic country in the heart of Africa without ever being able to get inside.

Congo marked the imagination of the Belgians. I remember the letters typed on blue airmail paper that we were receiving from a great-aunt who was a missionary nun in the Congo. More recently, my children chose to write their high school final essays on the controversy surrounding Tintin in Congo and the role of Katanga’s uranium in creation of the first atomic bombs at the end of World War II.

Finally, this summer I got the opportunity to go to Kinshasa for a week. I was told that it would be chaos. This is not what I experienced. Maybe I was lucky, maybe the contrast with the other African cities that I often visit was not that stark, or maybe the “robocops” placed at the main intersections– a kind of hybrid between policemen and traffic lights – were doing their job well in regulating traffic? In Kinshasa, a short detour is enough to come and pause along the Congo river. There is enough greenery along the banks to believe that you are outside the city, even though I didn’t see any pirogues and Brazzaville’s high rises can be spotted on the other side.

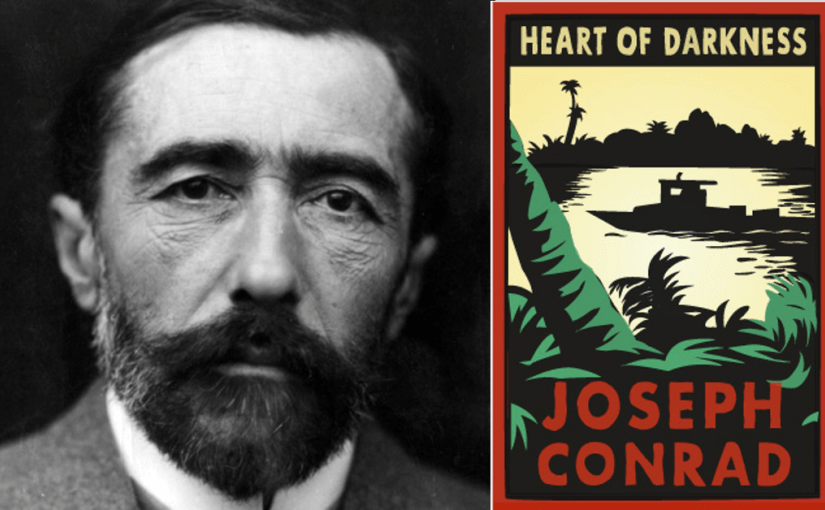

The river imagery associated with Congo might come from Joseph Conrad’s book « Heart of Darkness ». It is one of the great classics of the English literature, written in 1899, at the beginning of the colonial era when the Congo was the private property of Leopold, King of the Belgians. This is the story of the first white men arriving to exploit the country, going upstream on the river until they completely lose their marbles (the novel was the inspiration for Francis Ford Coppola’ Apocalypse Now who transposed it during the Vietnam war). The novella is often read from a psychological angle, but it can also be understood as a denunciation of colonialism’s excesses.

Nevertheless, this book, perhaps because of its title, also probably because in it the Congolese only have a very marginal role, contributed to give to Africa, and in particular to Congo, the country at its heart, the image of an inaccessible continent, dark, wild where the white man comes to lose his bearings and his reason.

« A Burnt-Out Case » by Graham Greene might at first seem to offer a contrast with Conrad’s book. At the end of the colonial period, a European architect, famous but fleeing scandal, goes up a Congolese rive aboard a ship to find refuge in a leprosery. He just wants to be forgotten while helping the doctors and the missionaries. But despite his wish to lead a calm and recluse life, scandal and drama catch up with him. It is an excellent novel, but once again the Congolese only appear as background, as lepers and drivers.

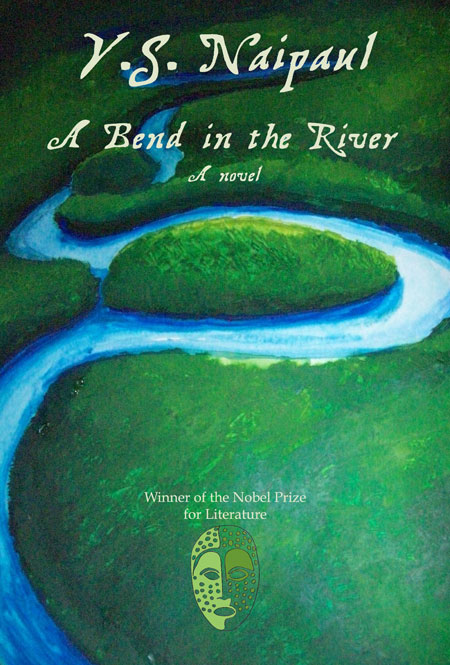

« A Bend in the River » – proof that it is difficult to escape the river imagery – is considered as one of the masterpieces by V.S. Naipaul, the recently deceased Nobel Laureate. It tells the story of a tradesman of Indian origin who establishes himself in a small town in Zaïre at the beginning of the Mobutu era. He starts to interact with and observe the Belgians and the Zairians. He describes a country that gradually descends into chaos, decrepitude and the cult of the « Big Man ». If Naipaul, born in Trinidad and of Indian origin, can, like his narrator, claim to escape the colonizer/colonized dichotomy and propose a new angle, he was criticized for his pessimistic look on the years after the Independence.

In « The Poisonwood Bible », the American novelist Barbara Kingsolver addresses the same crucial period before and after the Independence in 1960. An American family arrives from Georgia in a small Congolese town, along a river. Nathan Price, the father, is a Baptist minister whose missionary efforts will come to a hard crash: his uncompromising zeal leads nowhere, while his wife and four daughters try to adapt as best as they can to their new life. If the father’s character, sinking into madness, can be reminiscent of the « Heart of Darkness », the women in the family, especially the four girls, give a very different outlook. Each in their own way try to understand this country discovering its independence and get in touch with the inhabitants. One of them, Leah, marries the village’s teacher.

« Congo. The Epic History of a People » by David Van Reybrouck is not a fiction work, but I turned its pages like it was a novel. While articulating masterfully the great lines of Congo’s history, it highlights the daily lives and struggles of the Congolese during the many upheavals experienced by the country.

Over time, the writers inspired by the Congo have given more space to the people living in the country. But in the end, nothing replaces reading a novel written by a Congolese author. « Tram 83 » by Fiston Mwanza Mujila describes the exuberant atmosphere of the eponymous bar, a gathering place and watering hole for miners, students, foreign businessmen and whores in a mining town in the country’s interior. Lucien, idealist and would-be writer, is duped by the cynical Requiem, the miners still risk their lives for a few francs and the young girls continue to join the ranks of the prostitutes. In short, not much to celebrate, but nevertheless, every evening the « Tram 83 » fills up, the music and the beer are good, and the party goes on.

Far from the pirogues crossing the river at sunset…